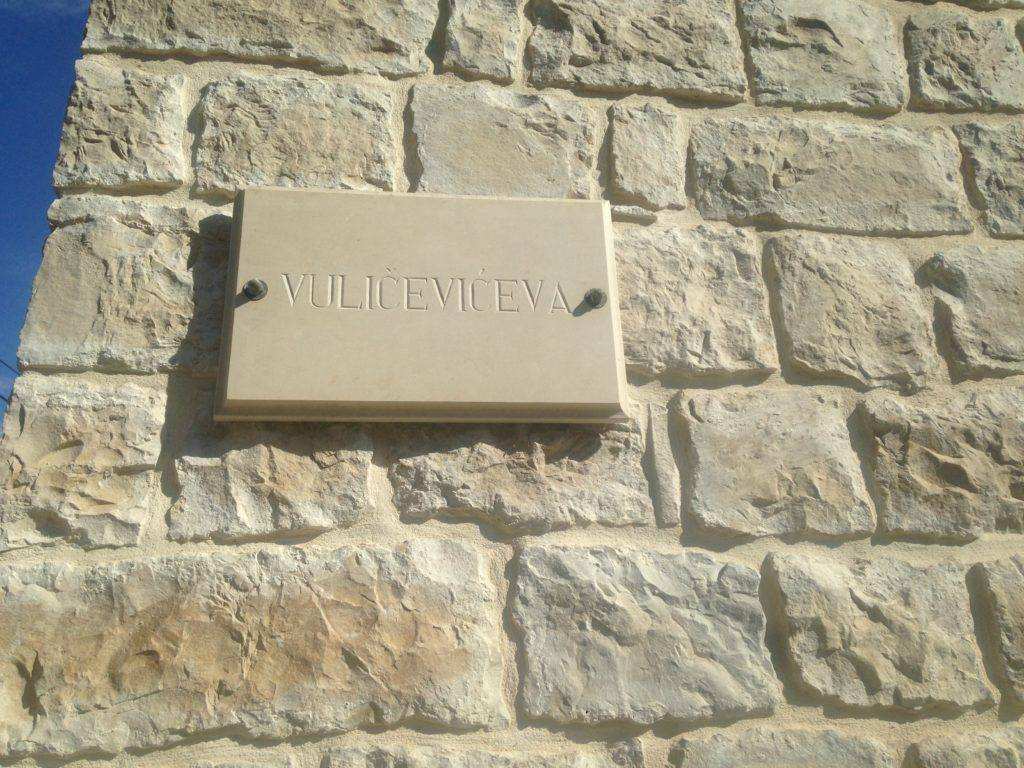

`Neither does freedom associate with force, nor does love associate with hate, nor does light associate with darkness.‘ This quote reflects on the nature of freedom, much like the following one: `Freedom is measured and valued in relation to slavery, as is slavery measured and valued in relation to freedom.’ Both quotes are especially relevant today. Is this global pandemic which is currently affecting us truly so threatening that it justifies the limitation of our rights and freedoms, or is it merely used as an excuse for the suppression of human rights? Or are we subjected to yet another conspiracy theory scenario? These questions have been in the media spotlight for quite some time now. And judging by the above-mentioned quotes, the issue of freedom was also a topic which fascinated their author, Ljudevit Vuličević. At the same time, this is an opportunity to reflect on the individual after whom the first street in Cavtat (as viewed from the western side of the city) is named, as well as on all the historical trivia hidden in Vuličević Street, also referred to as `Rustle Street’ by the locals.

Ljudevit Vuličević was born in Cavtat in 1839; he led an extremely fascinating life, filled with constant questioning of both himself and his environment, his nationality and, above all, the notion of freedom. His baptismal name was Petar, the birth register states that his father was Niko Papi, while his mother’s surname was Vuličević. The single mother entrusted the care of Petar’s education to the Franciscan monks. He was educated in Italy, in Barbarano, where he was most likely ordained and named Ljudevit (Lodovico). In 1862, he returned to the Franciscan monastery in Dubrovnik. Not long after, he travelled as a missionary to Albania. The historical sources from 1871 indicate that he served in Pula at that time, no longer as a Franciscan monk, but as a diocesan priest, while also working as the editor of the Il Pensiero journal, the newspaper for the working class whose aim was to strengthen the unity and solidarity among the Pula workers.

He later moved to Trieste, where, having left the Catholic Church and becoming its bitter critic, he became a writer and worked as a private tutor, while also collaborating with the liberal newspaper Il Cittadino. However, that would not be the end of his exploration of religion, as he later became a priest of the Protestant Waldensian Church, living and preaching its teachings in Taranto, Brindisi and Bari. Through his literary works and newspaper articles, he declared himself a Serbian Catholic, which was an interesting phenomenon in Dubrovnik’s political scene in the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He passed away in Naples in 1916.

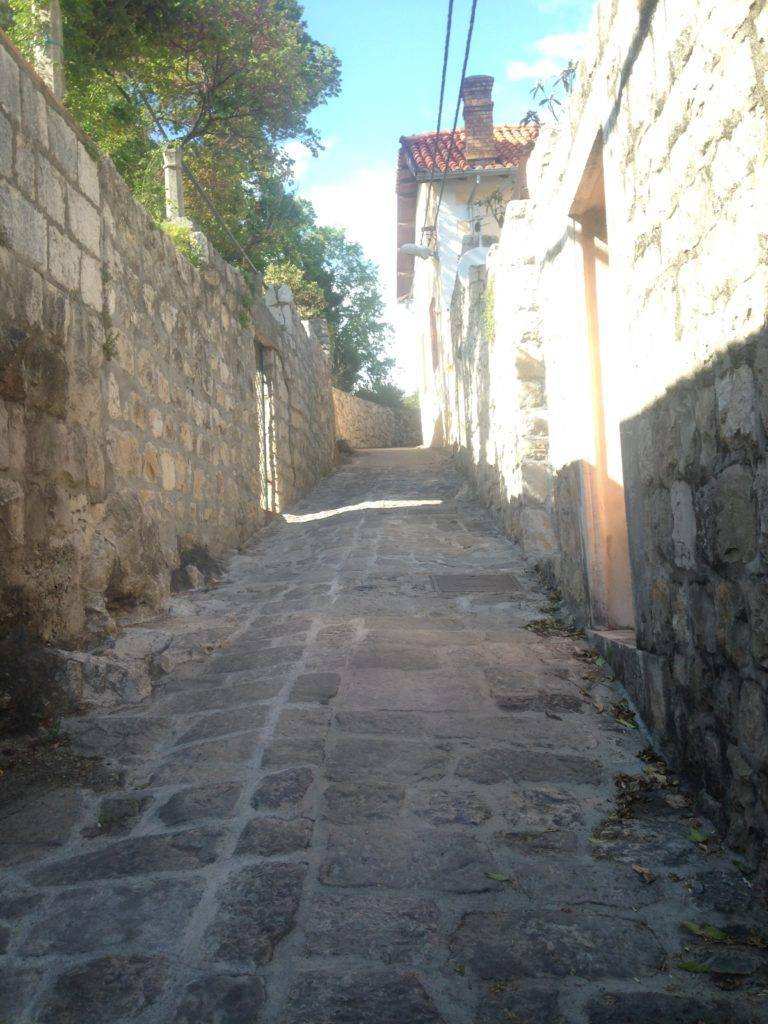

Such a colourful character deserves a colourful street, and this is definitely Ulica od šušnja. It is the only street in Cavtat not levelled with steps and is the sole street providing vehicular access to St Roch Cemetery. The street was once lined with ivy, which in some places created tunnel-like passages, and the whole street was covered with leaves, which gave it a special atmosphere. It is possible that the ancient cardo street also coincided with this street; if not, the street certainly provided a large number of ancient finds. In the garden of the Burđelez family house, the remnants of the water supply system were found. The Reverend Father Niko Štuk, the parish priest of Cavtat at the time and an archaeology enthusiast, referenced these remnants in his writings as early as 1908. Moreover, he also mentioned the foundations of certain buildings in that same street.

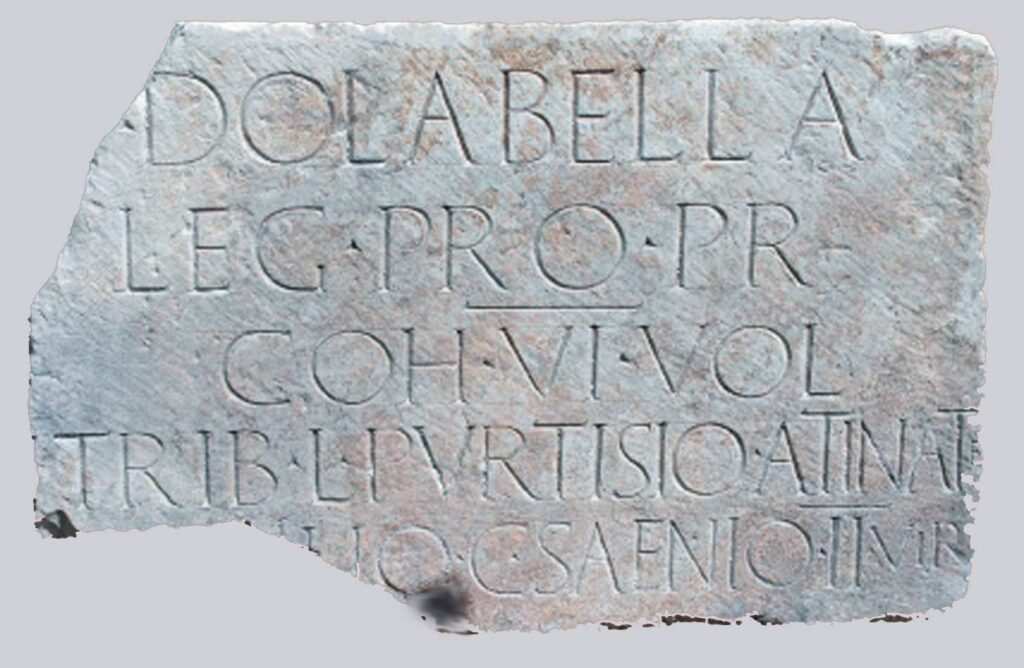

In Vuličević Street, an extremely important fragment of a stone monument was found with an inscription that mentions the name of the governor of the province of Dalmatia, Publius Cornelius Dolabella, the Roman military unit Cohors VI Voluntariorum and its commander Lucius Purtiziius Atinas, and the names of two city magistrates who most likely probably testified to the realization of a large infrastructure project, the name of which must have followed in the missing part of the text, financed by the Roman imperial treasury. The inscription was placed after the construction project’s completion, and it can be assumed that it took place between the years 14 and 20 C.E., during Dolabella’s governorship. The recent reconstruction of the house where the inscription in question was uncovered testifies to the lack of appreciation for history on the behalf of the investor. Namely, according to the later statements of the workers who were present on the construction site every day, and who were at the time forbidden to disclose the details of what was happening inside the enclosed area in which they worked, a large number of archaeological findings were destroyed. Such a pity! We will forever be deprived of the answers to some important questions concerning the everyday life of the ancient city which once stood in the place of Cavtat.