Roman provincial cities typically were the centres of the annexed territorial units organised and divided among the Roman colonists. State land (ager publicus) was created by confiscation of land; however, such areas were not under direct jurisdiction of the state. By retaining their sovereign right, the state would bequeath them to the administrations of municipal communities, provided that the land was cultivated and the communities in question paid certain taxes.

The colonial ager was used by the communities of agricultural producers and thus formed the economic foundation of cities. The Romans viewed life and work on the land as the noblest way of life, and the possession of the land as a true treasure; this is confirmed by a proverb by Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 B.C.E.), `For of all gainful professions, nothing is better, nothing more pleasing, nothing more delightful, nothing better becomes a well-bred man than agriculture.’

With regard to its classification, there were three types of ager: state (ager publicus), private (ager privatus) and uncultivable (ager compascuus), i.e. a common grazing land. The size of the territory which the state would allocate for ager publicus was not regulated by any laws; it was determined on the basis of not only the quality of the land, but also the relations between the territory in question and Rome. Private ager did not concern the state until it was necessary to resolve disputes over property lines or the ones concerning the right of possession. On the other hand, ager compascuus refers to grazing land and uncultivable land such as forests. This land was not divided and its boundaries remained unchanged following the Roman conquest. Therefore, this ager was public property and could not be alienated or privatised.

The colonial ager was divided into centuriae, which in the time of Augustus (27 B.C.E. – 14 C.E.) measured 710 metres (approximately 2330 ft) per side of the square. They were called centuriae because each of these squares contained 100 jugers of land; juger was a Roman unit of area denoting the amount of land which could be ploughed by a pair of oxen in a single day. The boundaries of centuriae were delineated by dry-stone walls. Epidauritan ager, when compared with those of Poreč (Parentium), Pula (Pola), Zadar (Iader) and Solin (Salona), was among the smaller agri on the east coast of the Adriatic. Ager Epidaurum most likely stretched from Slano in the west to the Bay of Kotor in the east, while the colony in question was also probably given a part of the land in the hinterland (Trebinje, Panik, Miruše…).

According to the latest calculations, the Epidauritan ager was divided among 173 colonists-veterans, of which 13 were cavalry men and 2 were centurions, while the rest were soldiers. Namely, following the discharge from military service (the average duration of Roman military service was approximately 25 years), veterans were given land so that they could lead comfortable civilian lives; the allocation of the land was done via the deduction of the colony. The army had at its disposal a certain part of the state land, on which the veterans would get a small plot of land. Having received the land, most veterans still did not live permanently in the countryside, instead choosing to reside in the nearby urban centres, while producing food in the countryside in order to ensure further sustenance.

It cannot be said with certainty what types of crops were grown on the Epidauritan ager. However, taking into consideration the knowledge of other Roman agri in the Mediterranean, it can be concluded that cereals, vines and olives were grown, forming a typical triad of agricultural products which is still present in parts of the Konavle Valley. With regard to the irrigation of the Konavle part of the ager, several streams passed through the region, while the irrigation of certain areas was additionally supported by the water supply system connecting the present-day village of Vodovađa and Epidaurum (Cavtat). This can be confirmed by the traces of ceramics and ancient tegulae (roof tiles used for covering villae rusticae) uncovered along the aqueduct route.

Ancient aqueducts, especially the Roman ones, are among the most complex and expensive infrastructural buildings; from the construction, geodetic, urbanistic and sanitary perspective, these structures speak of the technical and scientific ingenuity of their builders. It is estimated that approximately 200 aqueducts were built on the territory the Roman Empire, while Rome alone had 11 such water supply systems.

Vitruvius, who accumulated his architectural and construction knowledge in his treatise On Architecture published near the end of the 1st century B.C.E., dedicated the entire seventh book of the aforementioned treatise to water and water supply. The book in question reveals the methods of testing the quality of drinking water in antiquity; moreover, it discusses rainwater, watercourses and thermal springs, but most importantly, it elaborates on how aqueducts were built and levelled.

The scarce remains of the Epidauritan aqueduct are to this day a testament to an exceptional engineering undertaking that most likely took place at the beginning of the 1st century, during the governorship of Publius Cornelius Dolabella over the province of Dalmatia (14-20 C.E.).

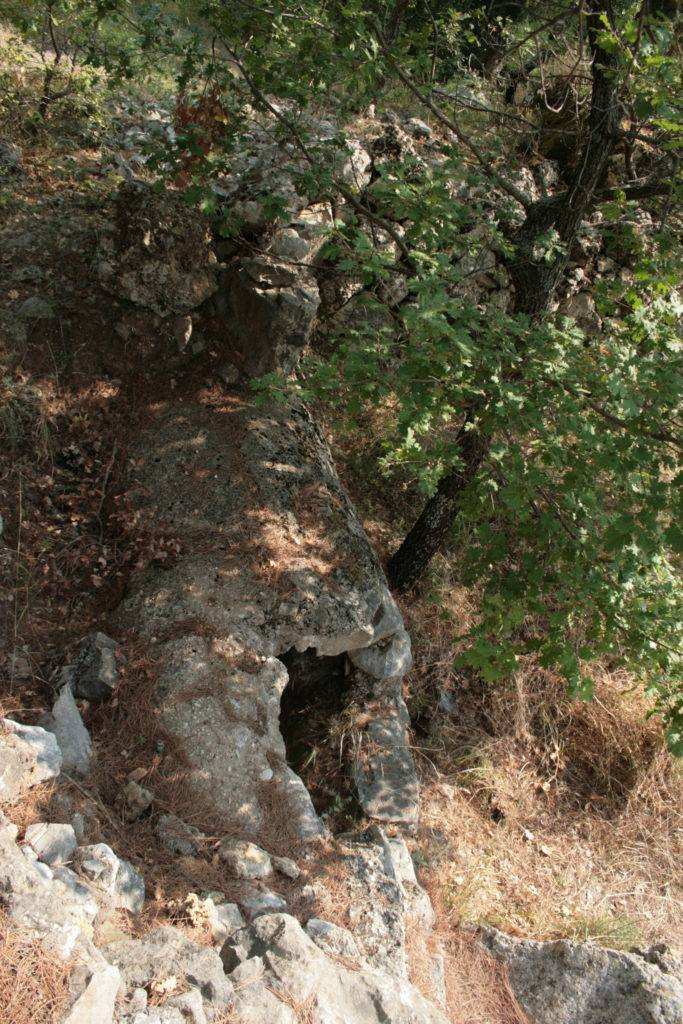

The water supply system was traced along the northern side of Konavle in a sinuous pattern, following the configuration of the terrain, which led to various solutions regarding the construction of the gravity canal. It was predominantly a ditch, however, where the terrain featured a steep slope, the gravity canal was elevated by a masonry substructure in order to maintain the required levelling of the bottom. Evans also writes about the remains of the arcades which were once erected at the very entrance to Cavtat in order to bridge the terrain; the arcades in question were demolished for the purpose of widening the road prior to the visit of Emperor Franz Joseph in 1875. These structures were built from a mixture of plaster, crushed stone and brick. The remains of the canal substruction in Knez Domagoj Street in Cavtat are still visible. The most well-preserved section of the water supply system is located in the village of Lovorno. Since it has been preserved in full profile, the aforementioned preserved section indicates that the canal was vaulted.

Built from carved stones of irregular shape and size, the inner part of the canal, the bottom and the side walls are lined with a thick layer of hydraulic plaster. The lower corners of the canal itself are slightly sloped. The outer walls of the canal are also plastered, while the diameter of the canal is 1.35 metres (approximately 5 ft). On the north side, the canal was once covered with earth in order to be protected from not only heat, but also from torrential waters.

A protection zone was established along the entire stretch of the water supply system. The terrain on both sides of the aqueduct (walled springs as well as canals and reservoirs), was to be clear and passable for the purposes of works and repairs. The water delivered to the city in this way primarily supplied public fountains or wells and was free of charge for both the citizens and visitors. By acquiring a permit, a private individual could connect to the public water supply network by installing an additional pipe and would be charged with a water rate.

The fact that Konavle (lat. canāle, canālis – “a canal”) was named after this exceptional construction project should motivate both the local residents and tourists to show more respect and care for the scarce remains that can be found along the entire water supply route from Vodovađa across Zastolje, Ljuta, Lovorno, Pridvorje, Mihanići , Gabrile, Uskoplje, Zvekovica to Cavtat.