There is no lack of wind in our sea, along with no lack of surface waves, storms surges or currents. Surface waves are those created by the constant blowing of the wind, and are also locally called živo more (the living sea). Mrtvo more (the dead sea), also known as zibni valovi (the rocking waves), are those that exit the zone of wind. The change in wind direction affects the weather at sea accordingly. Wind changes are more frequent in summer than in winter, so the dead sea and the living sea can merge and create a new challenge for all sailors and fishermen. Apart from the living and the dead sea, there is a tidal wave here and there, while the Adriatic is also no stranger to the rising tides, which are a consequence of the stormy south.

All seas have their current zones, i.e. seasonal current zones, their bays with calm waters providing safe harbours, as well as parts of the open sea which may or may not be navigable. Local fishermen knew their local posts, and sailors knew the nearby sea lanes. However, oral tradition created routes and ways of travelling the sea that were paid with human lives. The maritime industry was a necessity because the sea was the main trade and business route, while also facilitating all interactions with the neighbouring countries. The Mediterranean has been an area of maritime activity since prehistoric times, and the inhabitants of the Mediterranean have been those who sailed the seas at all times. This is supported by the data on shipwrecks which occurred along the eastern Adriatic coast, where more than 2,000 ships are estimated to have sunk in the last 3,000 years.

Over the course of centuries, shipbuilding techniques were perfected, and new discoveries and trade contributed to better navigation. Many cities had their own fleets, and Dubrovnik was in the lead in that regard. With its trade ties, numerous consulates around the world, especially in the Mediterranean and the Balkan countries, everything that Dubrovnik was involved in depended on sailing. Crossings to the west coast of the Adriatic were a daily occurrence for the people of Dubrovnik, and trade connections with the Levant were well-documented routine travels.

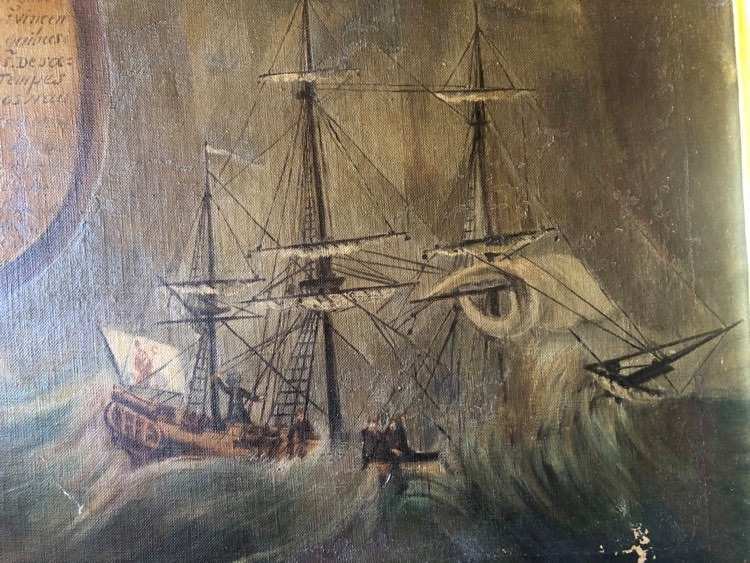

Dubrovnik seafaring in all its glory relied on a very developed fleet of large sailing ships until the beginning of the 17th century. In the 17th century, medium-sized merchant ships carrying from 100 to 300 kars (kar was an old Italian unit of volume), featuring two to three sails, were the vessels predominantly used for sailing the Mediterranean, while barques and yawls were the predominant types of sailboats. The front masts had a cross sail, while the stern mast had a lateen sail. In the 1720s, the people of Dubrovnik abandoned the use of large sailing ships and began opting for smaller ships. Galleons carrying up to 1000 kars could not manoeuvre in ports as well as smaller merchant ships; in fact, they could not even enter most French ports. Smaller ships filled up and emptied faster, so they sailed more often and stayed in ports for shorter periods of time.

Dubrovnik’s large merchant sailing ships, as well as the smaller barques, travelled from Ancona to Rhodes, Syria, Alexandria, Beirut, Gallipoli, Constantinople, especially in winter, while they preferred to travel to Romania in summer and early autumn. The sailing ships called barques, primarily those with a single sail, were the inventory of all small ports not only on Pelješac and in Primorje, but also in Cavtat, which served as an important port for the connection with Dubrovnik.

With the addition of Konavle to the Republic of Dubrovnik, the number of Konavle residents engaging in seafaring is slowly increasing. At the very beginning of the 18th century, the people of Konavle owned the most long-distance merchant ships in the Dubrovnik navy. Around the middle of the 18th century, they were the second most numerous sailors in the Republic of Dubrovnik (the first being the Pelješac residents); however, the Konavle sailors had the highest number of captains. The 18th century was a century marked by the rise of Cavtat shipowners, which will be stopped by the Napoleonic Wars. Namely, the events of the war destroyed the entire Dubrovnik merchant navy; as a result, the shipowners became impoverished and the sailors lost their jobs.

In the first Austrian census in 1818, there were only 34 smaller vessels in Cavtat, i.e. in the entirety of Konavle. Unfortunately, it is not known whether these were just fishing boats or smaller ships, but it is certain that these were not the long-distance ships typical of the 18th century. The situation would slowly improve by the middle of the 19th century, when ships with the carrying capacity of over 100 tons would reappear in Cavtat. However, the long-voyage ships had completely disappeared; as a result, the 19th century saw the ships of the Konavle residents mostly transporting passengers and goods only across the Adriatic.

As already mentioned, at the end of the 18th century there was a large number of sailors in Konavle, as well as of captains and other trained naval personnel. With the disappearance of the Dubrovnik navy, the majority of them were forced to find other types of employment in order to make ends meet. These circumstances are the reason for the first major migrations of Konavle people. The Konavle sailors seem to had been the most sought-after sailors on the ships sailing across the Levant; the most common migration destinations were Alexandria and Constantinople. Apart from seafarers, other people from Konavle also emigrated to those cities at that time, but it seems that the seafarers’ migrations had set in motion the migration wave to the Levant.

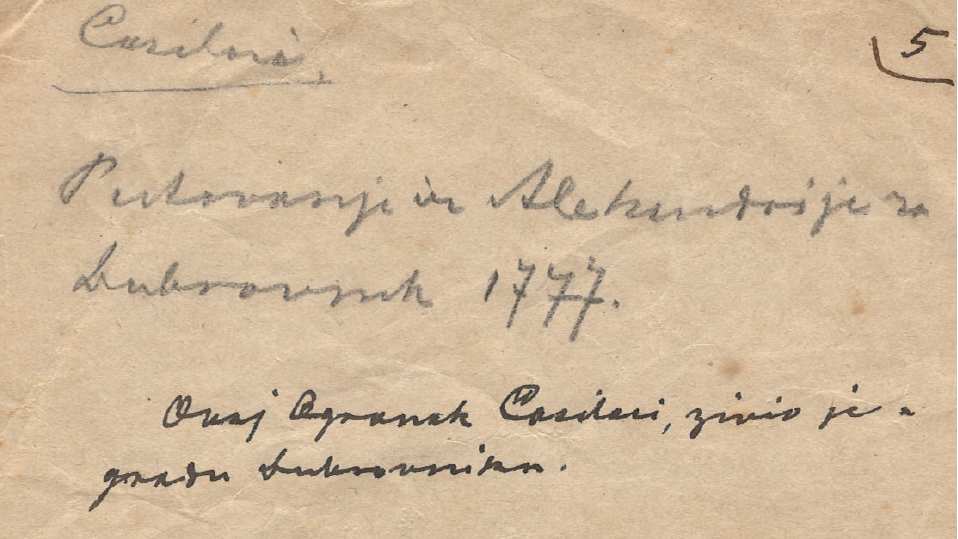

The Cavtat and Konavle captains’ families, as well as the shipowners’ ones, found themselves in a dire economic situation; nevertheless, throughout the 19th century, they struggled to restore the old splendour of their ships; Antun Casillari was a member of one such family. From the 18th century, one can follow the ship-owning activity of this family, which would form several branches by the beginning of the 19th century. The first census of shipowners shows the Casillari family (their surname was Kazilari until the 18th century, when they italianised their surname) as one of the families with the largest number of shipowners; throughout the 18th century, they would produce six captains and patruns (merchant ship commanders) and a large number of helmsmen and ship carpenters. In the 19th century, the Casillari were one of the most numerous families in Cavtat; in addition to shipping, they were engaged in trade and politics. The existence of many branches of the family resulted in several Cavtat residents bearing the name Antun Casillari at the same time in the 19th century; consequently, this has led to the confusion concerning the study of their respective lives and work. The Antun Casillari mentioned throughout this text was mostly referred to as “Captain Antun Casillari” in the records of the time.

The idea of educating seafarers in Dubrovnik dates back to the Middle Ages. Namely, although many intellectuals at the time, including Benedikt Kotrulj, considered seafaring a craft to be learned in practice, the need for education from an early age was recognized. The idea was for captains and other qualified sailors to raise a new generation, and the Dubrovnik government itself encouraged the boys to become deck boys intended not only to serve the captain but also to learn from him. It appears that in the early modern period there were certain maritime courses in Dubrovnik, but the skills in question were still predominantly learned in practice. It was only at the end of the 18th century that the first naval school in Dubrovnik was opened, but it did not last for long.

The maritime tradition of many Dalmatian cities, especially of Dubrovnik, was intended to support the opening of maritime schools in the early 19th century, but the plan failed due to lack of funding, qualified staff and available facilities. Since there was no state education, private individuals opened nautical courses. The courses were designed to prepare young men for the difficult situations at sea in which they may find themselves and teach them basic maritime skills. One such course had been held by our Antun Casillari in Cavtat since the middle of the 19th century. For some time, the maritime course in Cavtat was the only educational institution for the Konavle residents who wanted to become sailors.

Several generations of Konavle residents have passed Antun Casillari’s maritime course; the most notable attendee of his course was Vlaho Bukovac. Bukovac’s life was full of adventures, of which the most interesting is certainly the maritime one. Having returned from America, he completed a nautical course held by Casillari and prepared for his first marine cadet job: `My father approved my idea and sent me immediately to Antun Casillari to instruct me in seafaring. Mr Casillari was not a naval captain, but I can say that he was a good teacher.‘ Although Vlaho, like many other Konavle residents, would ultimately choose a different path in life following a brief stint at the sea, the course held by Antun Casillari allowed him to venture out into the wide blue sea, and the knowledge he received there probably saved his life on numerous occasions.