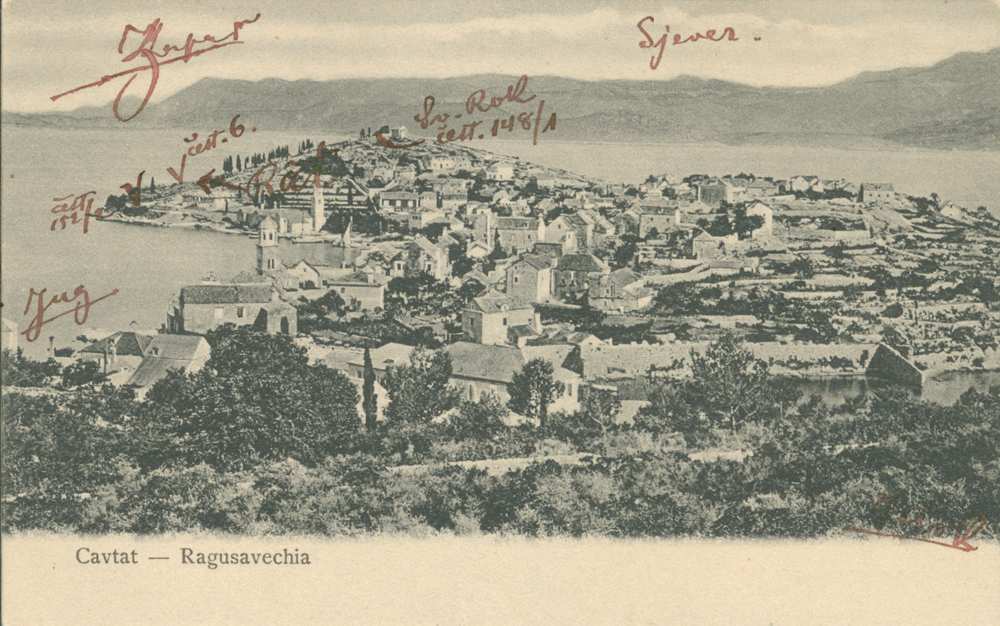

`The ruins of ancient “Epidaurum” are well worth exploring‘, wrote Ivo Kunčević, a member of the Dubrovnik branch of the Croatian Antiquarian Society, on 15th July 1929, suggesting that all previously known archaeological sites related to Epidaurum should be shown on a unified topographic map. Among the localities mentioned by Kunčević, there are also archaeological remains on the Rat Peninsula, known to the public since the first research conducted in 1907.

It was the local community’s interest in the antiquities from the Roman era and the history of Cavtat throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries which led to the popularisation of its archaeological heritage, primarily owing to the efforts of the Cavtat parish priest, the Reverend Father Niko Štuk, an amateur archaeological researcher himself. In 1907, together with several Cavtat residents – Gjorgji Bijelić, Ilija Račić, Luka Kalačić, Antun Bratić, Rikard Franičević and Ivan Guljelmović – he founded the Epidaurum Society – The Committee for the Excavation and Preservation of Epidaurum Antiquities.

In the same year, the Reverend Father Niko Štuk initiated archaeological research on the westernmost part of the Rat Peninsula, in an area which had been levelled with massive terraced retaining dry-stone walls throughout history, and the resulting terraces had been filled with large amounts of soil in order to create arable land. At the invitation of the society, the Reverend Father Frane Bulić, the conservator `in charge of the entirety of Dalmatia‘, as well as an archaeologist and historian, visited the site and gave them advice and guidelines for further research. Extremely interesting discoveries were made very quickly, which Reverend Niko Štuk himself reported to the professional public in the Bullettino di archeologia e storia Dalmata journal:

There is one well-preserved old wall, 37.6 metres (241 ft 5 in) long, 2-3 metres (6 ft 6 in – 9 ft 10 in) high, with three lateral decrepit walls, 3-4 metres (9 ft 10 in – 13 ft 1 in) long. Parallel to the aforementioned wall, situated 33 metres (108 ft 3 in) below, there is another wall of equal length, rising 60 centimetres (1 ft 11 in) above ground…

…After the first few blows with a pickaxe, a well-preserved pavement made using lime, pebbles and crushed brick concrete was revealed at a depth of only 75 centimetres (2 ft 5 in); not long after, a marble coating was discovered at the bottom of the inner wall, at the left end of the outer wall. Although the slabs with which the wall was covered were mostly broken off, and little of them remained, it can still be discerned that they were 1.18 metres (3 ft 10 in) long, 0.53 metres (1 ft 8 in) high, 0.018 metres (0,7 in) thick. The marble lining was 1.06 m (3 ft 6 in) high. The slabs are made of grey marble, properly cut and smoothed. They were tied together with copper hooks, some of which have been preserved. Slate tiles (ardesia) were placed under the slabs, while a 10-15 centimetres (4 in – 6 in) thick layer of cobblestone was placed under the slate. A piece of a broken stone pillar 0.71 metres (2 ft 4 in) high and 0.29 metres (11 in) wide was also found…

Due to problems with financing, the society temporarily stopped its research, but the support of the Central Commission for Monuments in Vienna, as well as of the Ministry of Worship and Education, owing to the recommendation of Reverend Frano Bulić, allowed it to resume research in 1911.

At a depth of 2 metres (6 ft 6 in), as Reverend Niko Štuk reports, various small objects were found. However, the owner of the land where the site was located protested and further excavation was stopped. The enthusiasm of the members of the society began to wane, and in 1912, Štuk complained to Frano Bulić that he and Gjorgji Bijelić were the only active members at that point and that his motivation to continue was slowly diminishing, citing the lack of understanding on behalf of the land owners as the problem. All this affected his health, and in the same year he requested retirement, since he `could not preach and research at the same time‘.

At the beginning of the First World War, the society’s work stopped completely. Although the research conducted by Reverend Niko Štuk revealed a representative specimen of a building, it took 73 years for systematic archaeological excavations to continue under the leadership of Romana Menalo from the Dubrovnik Archaeological Museum. The excavations began in 1984 and lasted until 1987.

During that time, several rooms, impressive fragments of architectural plastic, fragments of marble coating, ceramics and coins were discovered. After more than two decades, the research on this site was resumed in 2008 and 2012, with Romana Menalo acting once more as the head of the research group.

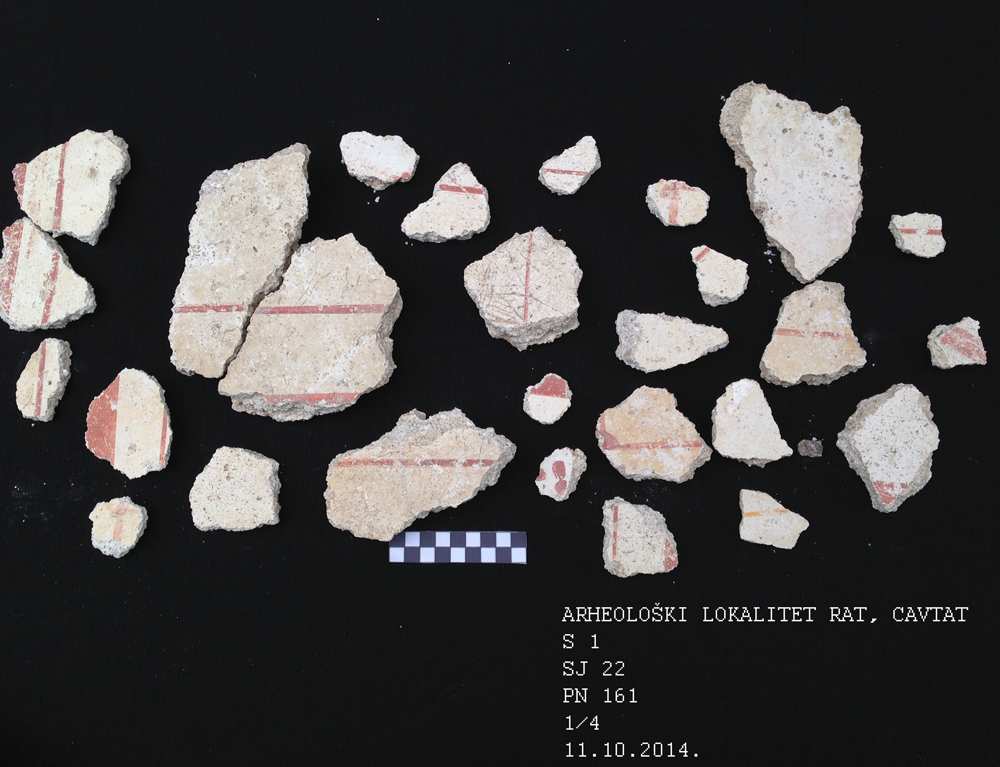

In 2014, the archaeological research conducted at the Rat site in Cavtat by the Museums and Galleries of Konavle revealed the remains of the walls on which fragments of plaster with wall paintings are visible in situ. A very interesting narrow room was discovered on the southwestern edge of the building complex, which was discovered in 1907 by Reverend Niko Štuk, and later explored by the Dubrovnik Museums over the course of several archaeological research projects. The part of the eastern wall featuring the remains of the niche, only partially visible during previous research, was completely uncovered; the remains of the northern and southern walls of the room and its exposed western part were also delineated.

At the western ends of the southern and northern walls of the room, the remains of well-preserved plaster with wall paintings were discovered. The discovery of a wall with remains of plaster and wall painting presents a special challenge for every archaeologist. During the uncovering, an internal cross-section of the plaster layers was made visible; it allowed insight into the composition and production process of the plaster base itself. The provided insight, in turn, revealed that the surface on which the wall painting had been made was of very high quality, consisting of three layers: two layers of rougher plaster called arriccio and the final, extremely smooth layer – intonaco.

As the insight into the production process of the plaster base at the archaeological site of Rat suggests, a tried-and-true recipe, written by Vitruvius as far back as the 1st century B.C.E., was followed. Namely, the first layer of coarse-grained plaster glued to the wall consists of lime, crushed brick, quartz and river sand. It is of reddish hue, as well as of extreme solidity. The second layer of plaster is of greyish hue, with the same composition as the first, but with more lime and a smaller amount of crushed brick. The final layer (intonaco) is extremely fine and very thin. A wall painting – a linear decoration on a pale pink, almost white background – has been preserved on the intonaco.

The remnants of thicker and thinner red lines are visible, featuring small stylized clusters at the corners; these clusters divided the wall surface into four equal parts. The arrangement of vertical lines suggests that the wall surface of the room was divided horizontally into three parts.

Furthermore, a large number of fragments of plaster with a wall painting, which fell off the decaying walls at some point in time, were found during the research. These are mainly fragments of plaster featuring motifs similar to those found on the intact remainder of the wall painting, but there are also fragments of plaster with visible traces of other colours such as ochre, green, blue and black. Curved lines are also visible on several fragments, so we can assume that there were also small, central figurative or floral, or perhaps even panoramic motifs painted within the parts of the wall framed by red lines.

Other finds, such as fragments of stucco decoration and multicoloured fragments of marble tiles, suggest that the upper part of the wall painting was decorated with stucco moulding, while the lower part of the wall, below the wall painting, was most likely decorated with marble panelling.

It can be assumed that this narrow and long room was barrel-vaulted; the assumption is supported by the large number of travertine fragments found at the site. This specific form of decoration as preserved on a fragment from the Rat site, the so-called `linear style’, appeared only at the end of the 2nd century, and is characteristic of the 3rd century.

Taking into consideration the fact that the other architectural and movable findings of this construction complex speak of its use and creation from the 1st century B.C.E: until the 4th century C.E., it can be assumed that the addition of this intriguing room took place in the 3rd century. These archaeological remains are a testament to the wealthy lifestyle of the residents of ancient Epidaurum.