As decreed by the law of the time, typical Roman necropoli were located outside the city walls. If there was space, city necropoli were divided into burial plots, but almost as a rule they were located along the main road leading to the settlement. As rare archaeological research shows, the necropoli in the Roman colony of Epidaurum were located in the same fashion.

Recent excavations in Cavtat’s Zore Street, as well as some previously known findings, confirm the location of the ancient necropolis on the northern side of the Rat Peninsula. Arthur Evans was among the first researchers to mention the ancient graves in that area in his book Antiquarian Researches in Illyricum, published in London in 1883. Evans writes that the oblong sarcophagi carved into the bedrock can be seen on the hill on which the St Roch Church is located, but he also mentions two tombstone inscriptions carved into the rock in the Tiha bay. These inscriptions are still visible today.

In antiquity, as in most historical periods, the final resting places or graves of individuals differed depending on the social status of the deceased, ranging from simple burial plots to rather complex architectural constructions.

The position and appearance of individual graves is what provides a breadth of information on the social status of the city’s residents, as well as on the direction of the roads leading to the city itself. Such is the case with these two tombstone inscriptions, which mark the position of the road that probably led from Epidaurum to Asamo (today’s Trebinje), and from there a little further north to Ad Zizio (Mosko), where it joined the main trunk road. That road connected Aquileia in Northern Italy across the hinterland of the Adriatic coast all the way to Dyrrachium (today’s Durrës) in Albania, from where it continued towards Constantinople.

The Epidauritan necropolis stretched along the northern side of the Rat Peninsula and along the road, across Tiha street towards Donji Obod.

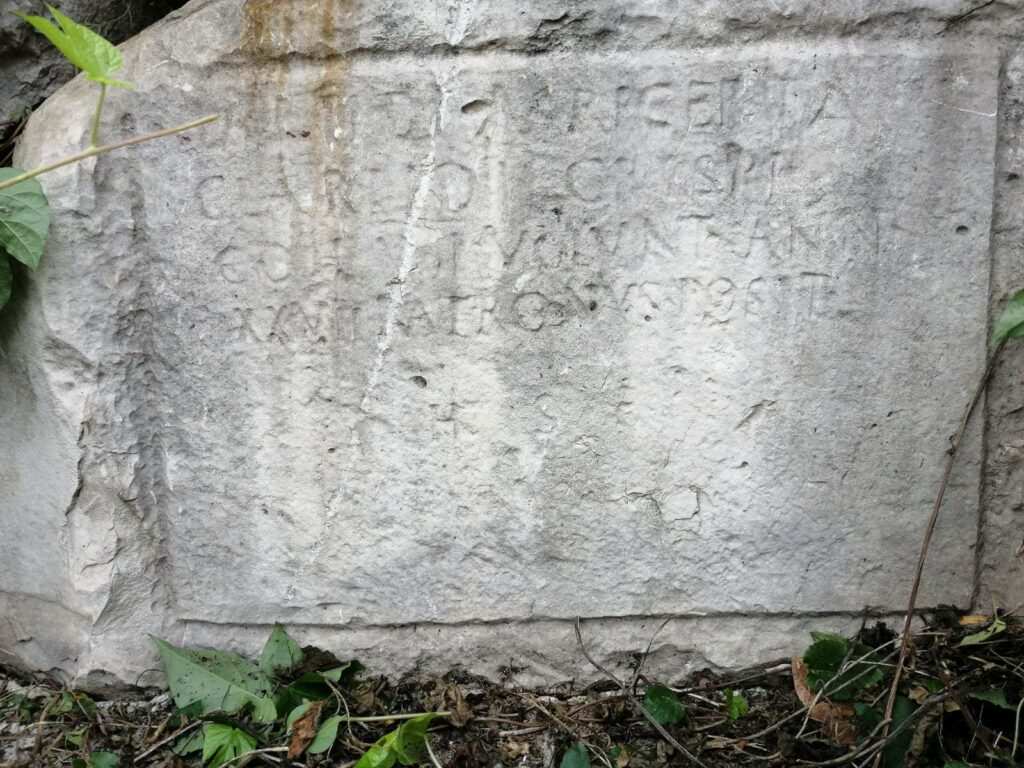

The aforementioned tombstone inscriptions carved into the rock at the cadastral parcel no. 469 say that two women were buried there. Moreover, they were probably slaves, one of whom was freed. Their names are Lartidia Recepta and Tertia. The monument to Lartidia Recepta, who, as the inscription reads, died at the age of 27, was erected by the patron Gaius Lartidius Crispus, a centurion of the Cohors VIII Voluntariorum military unit:

LARTIDIA RECEPTA

C(ai) LARTIDI CRISPI (centurionis)

COH(ortis) VIII VOLUNT(ariorum) ANN(orum)

XXVII POS(u)IT

H(ic) S(ita) E(st)

In accordance with the established practice of the time, Lartidia Recepta took the nomen (hereditary name) of her patron after being freed. Namely, she added the nomen Lartidia to her original name, Recepta. It should be noted that the naming conventions for slaves were not the same as those for Roman citizens.

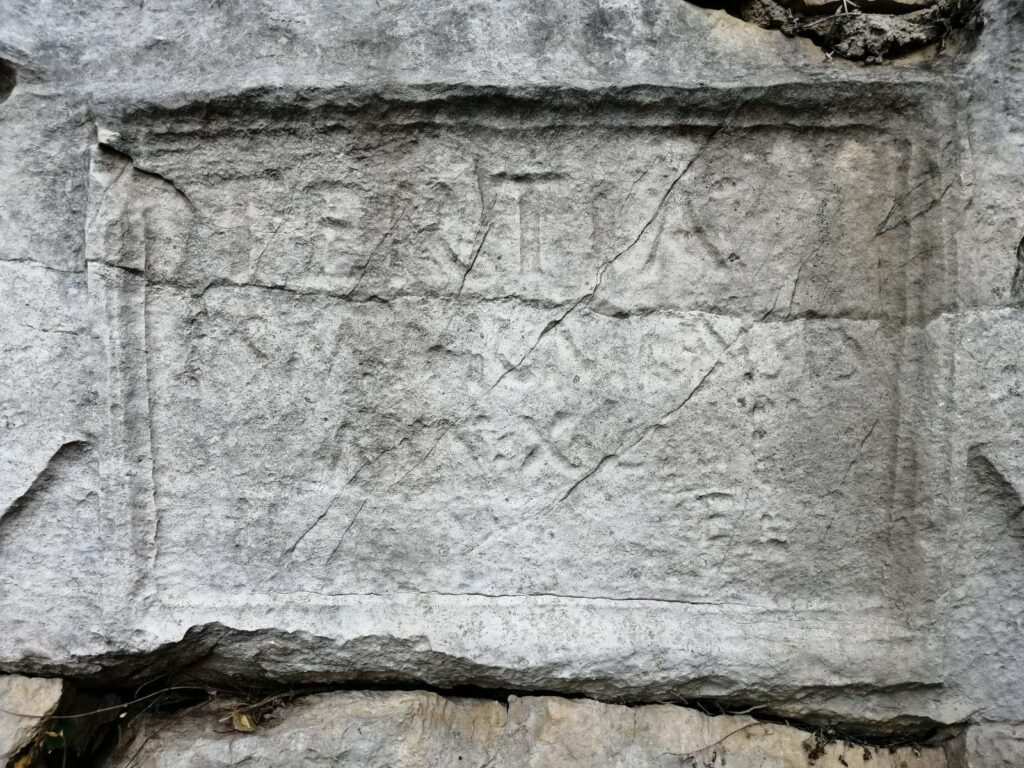

Therefore, the other inscription, located just a few metres away from the monument to Lartidia Recepta, informs the reader that it was erected in memory of Tertia, and since she is only referred to by a single name, it can be assumed that she was a slave. As the inscription reads, Tertia was a Thracian woman from Ismar who died at the age of 40:

TERTIA

ISMARNIENSIS

ANN(orum) XL

H(is) S(ita) E(st)

These are simple monuments, framed by ordinary rectangular strips. Of the two, Tertia’s inscription is slightly more profiled, and it appears that it once had two handles (ansae) on the sides. The ashes of these two women were probably placed in the urns located under the inscriptions themselves.

It is fascinating how much information is contained on these two seemingly simple monuments and how important they are in shedding light on the history of the ancient city. Therefore, an effort should be made to provide them with the necessary legal protection and appropriate signage.