`To him, a person can be either cherished or loathed. He is devoid of any pretence, and is rather inconsiderate in this regard. He either loves or hates. Anyone who has resented him once will hardly be able to get back into his favour. When he burns a bridge with someone, that ship has sailed for good, since he knows nothing of indecisiveness or conventionality – he closes himself off, forms his own judgment about the matter; sometimes his judgment is wrong, but once he has made up his mind, there is no changing it. He can only be disrupted by some fond, distant memory associated with a person with whom he is in conflict. In that case, for a few times he gives in, forgets the conflict, but not for the sake of the other person, but rather for his own sake, because that memory concerns him, because that memory is dear to him, so he cannot forget it.‘ This is what Božo Lovrić wrote about Vlaho Bukovac before he himself had a falling out with the famous painter.

Bukovac was happy to recount his tumultuous life to his family and friends in form of humorous anecdotes, but the events which he narrated were often dramatic life situations. And he had plenty of stories to tell. Exciting journeys and the impossible situations in which he found himself followed him since early childhood. Magazines of the time often published sketches of Bukovac’s life, while sometimes his biography would appear in the form of a short story, such as can be found in the collections of Simo Matavulj.

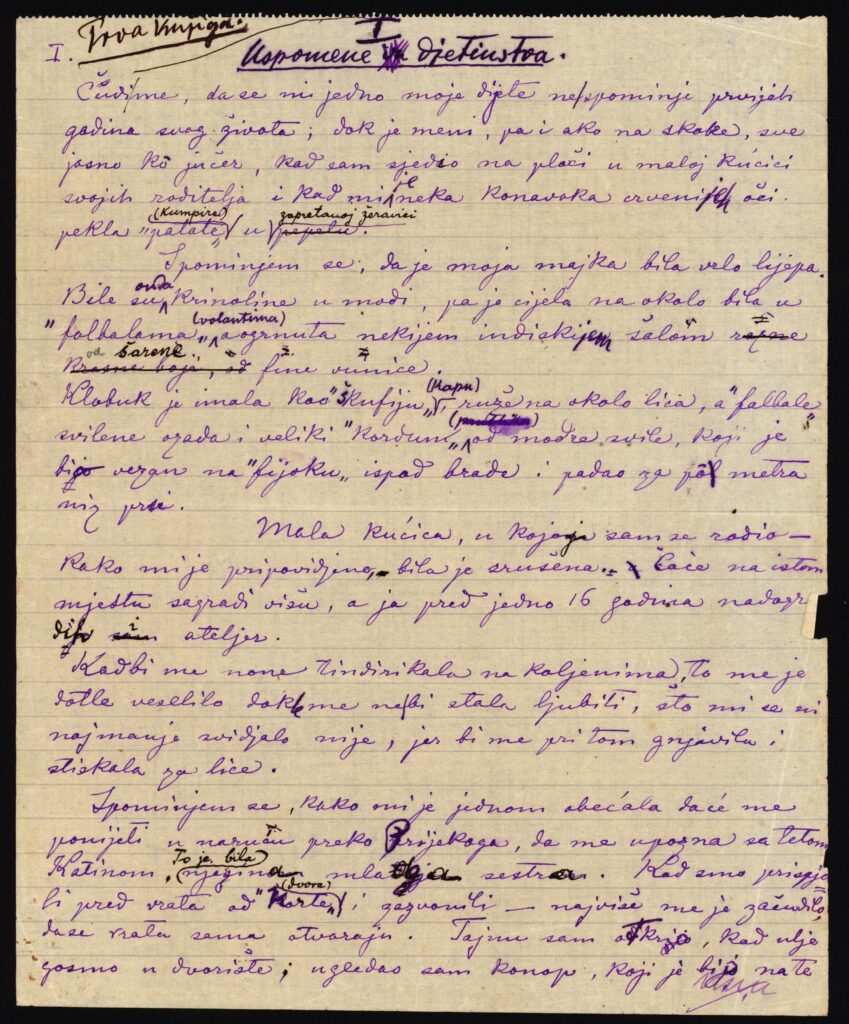

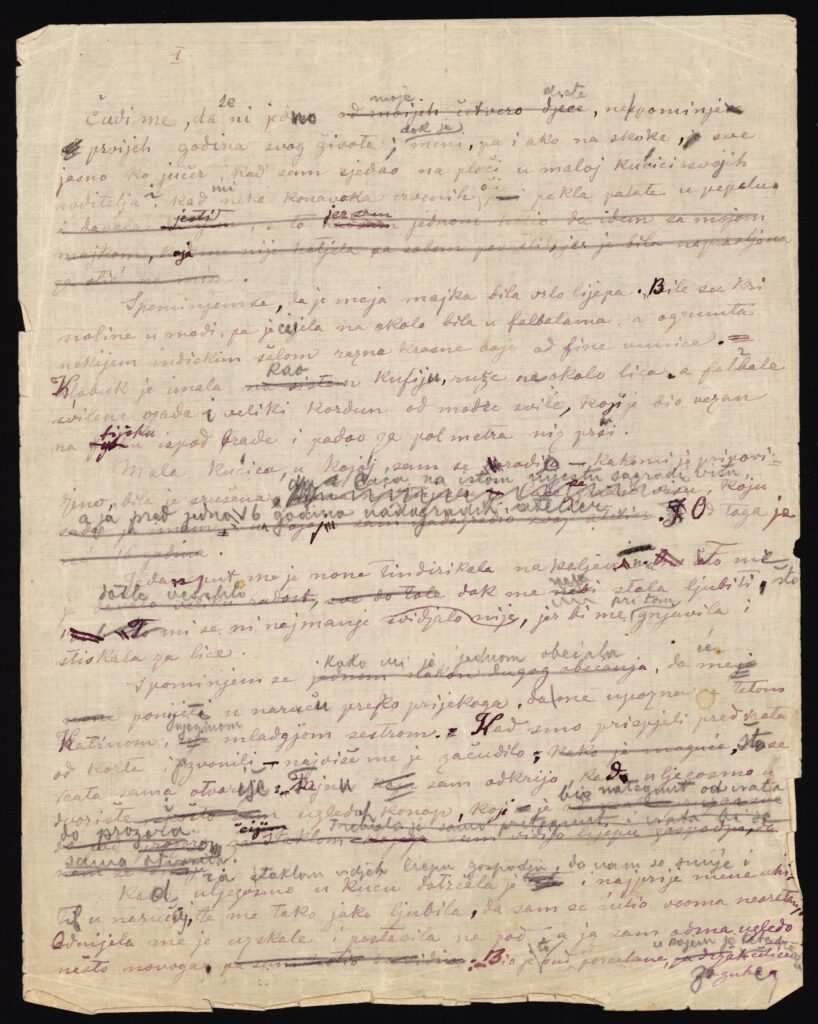

Ivanka Bukovac wrote in her unpublished memoirs that during the First World War – a period of introspection in which he was deprived of any travel – Bukovac was persuaded by his daughters to record in chronological order all the interesting stories he told them. Two manuscripts of Moj život (`My Life‘), and an autobiographical novel published by the Književni jug publishing house in 1918, are preserved in the Bukovac House. The foreword was written by Ivo Vojnović, while Božo Lovrić was the editor. Vojnović and Lovrić were the two writers who had one thing in common with Bukovac – their work was also linked to Prague at the time.

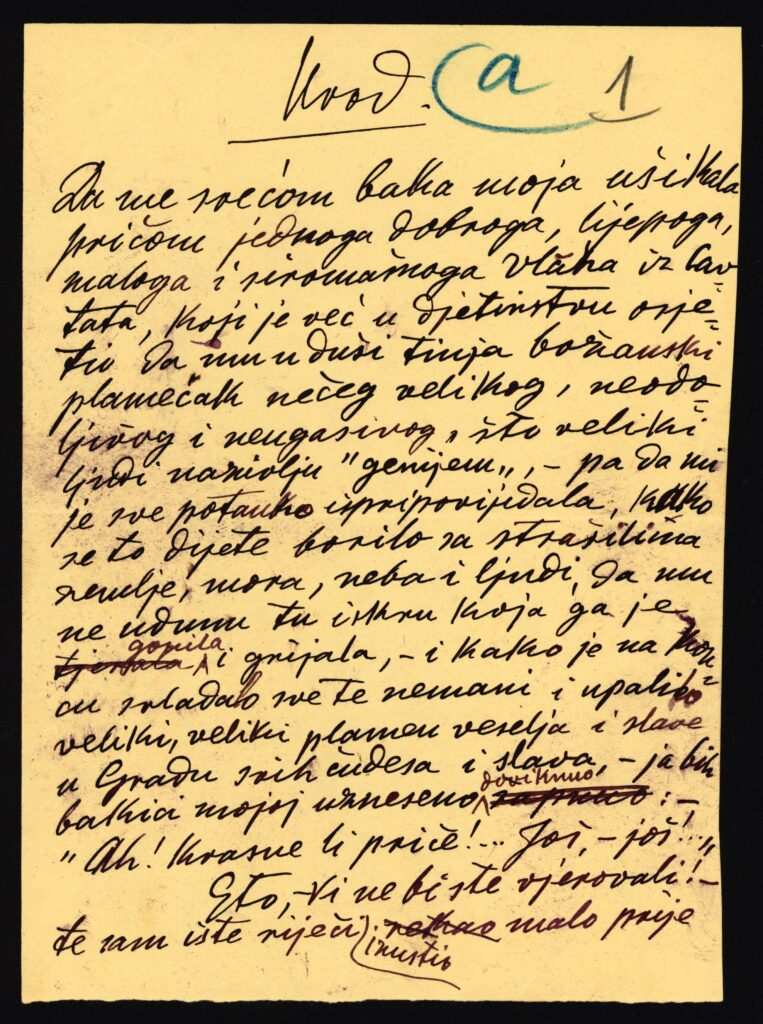

The feeling of amazement felt upon reading that incredible autobiography today was described by Vojnović in the first lines of the foreword:

`If only my grandmother could have lulled me to sleep with the story of a nice, handsome, poor little boy from Cavtat named Vlaho, who already in his childhood felt that the divine flame of something great, irresistible and unquenchable – of that which great people call “genius” – was smouldering in his soul. If only she could have told me everything in detail of how that child fought the horrors of earth, sea, sky and man in order to keep alive that spark which pushed him onward and warmed his heart, and how in the end he overcame all those obstacles and ignited a great flame of joy and glory in the City of All Miracles and Grandeurs, – I would have excitedly shouted “Ah! What wonderful stories! More! More!” to my grandmother. In fact – you wouldn’t believe it! – I uttered those same words to myself a little while ago, after I swallowed – yes, swallowed ad litteram! – My Life by our famous Vlaho Bukovac.‘

Indeed, My Life tells a life story which leaves no one indifferent. However, Bukovac was somewhat displeased with Lovrić’s editing. Namely, he thought that Lovrić had revised too much of the manuscript without his approval and that his original and direct writing style had been lost in the process. Therefore, he turned to his friend, the writer Marko Car, for help.

`I was overjoyed to have received your letter yesterday. I felt an immense joy that you accepted to revise the My Life manuscript for me, though I must admit I was hoping that you would be kind enough to do so. It pained me that I hadn’t listened to my dear Jelica and instead had given the editing task to Mr L. Even if his work was not so dreadful, my way of speaking and storytelling was permanently lost. And as you say, it would be good to preserve the character of my narration as closely as possible, I am convinced that your help will make the book much more beautiful and interesting. Of course, from the current perspective, even I would change some things, leave others, and add some details.‘ This is what Bukovac wrote from Prague to Marko Car as early as 19th December 1918, not even a year after the first edition release.

Be that as it may, Marko Car edited and wrote the foreword to the new edition, which wasn’t published until 1925, three years after Bukovac’s passing. Published in Belgrade and printed in Cyrillic, the 1925 edition has not had the same impact as the 1918 edition containing Vojnović’s foreword, which is still in print today.

The differences between the two editions of the book prompted the Bukovac House to provide the interested public with a truly unique experience – the opportunity to view and compare two manuscripts with one another, as well as with the 1918 edition of the book, while also viewing a handful of additional illustrations, which can be viewed in more detail on the Museums and Galleries of Konavle website.