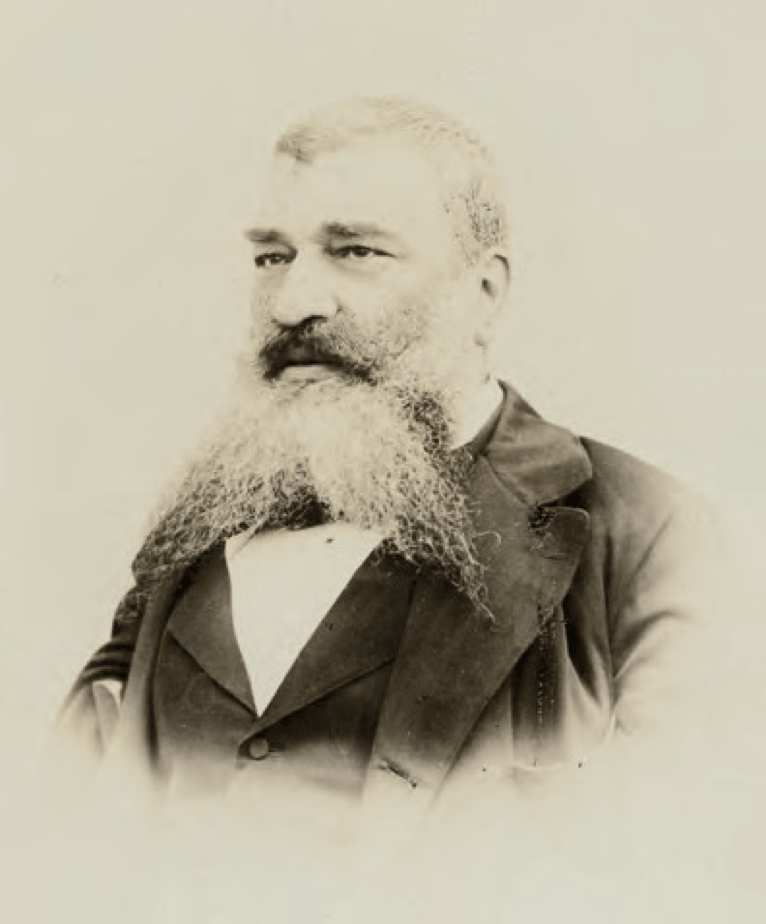

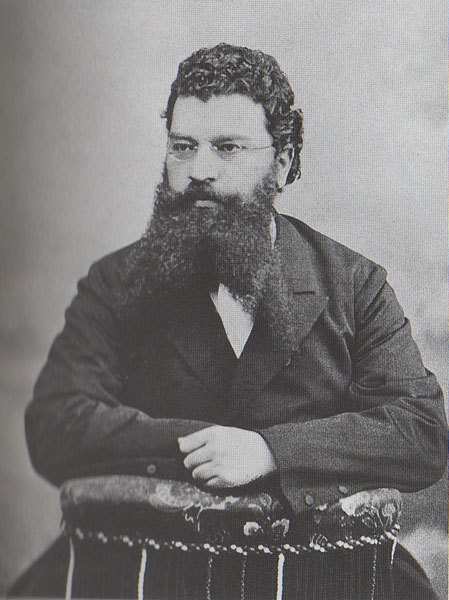

Cavtat was the place of origin for many political figures in the latter half of the 19th century. One of the more influential statesmen of that time is the now almost forgotten Luko Zore. During his lifetime, he would become one of the most important theoreticians of the Serb-Catholic Movement in Dubrovnik, and would be remembered in history as the editor of the Slovinac newspaper.

In 1907, Zore himself wrote an article concerning his early life in the Srđ journal. The aforementioned text reveals that his father Antun was born in Popovići in the beginning of the 19th century, but moved to Cavtat in 1839 and was a seafarer. Following his seafaring ventures, Antun opened a general merchandise store, and `when he was over forty, he married the Konavle resident Mara, who worked as a salesperson in one of the stores‘. Despite all the successes in life, the greatest misfortune for the Zore family was, in Luko’s own words, `the death of their children. Of the eight children, three remained alive – one of them being our Luko‘. It was on 15th January 1846 that little Luko’s life adventure began.

As he himself wrote, he started collecting letters and papers, which he jealously hid from his brothers, from an early age. It is likely that this children’s pastime contributed to the development of his interest in the written word. Following his primary and secondary education in Cavtat and Dubrovnik, he attended Slavic studies in Vienna. After completing his studies, he returned to his homeland and worked as a teacher at the Dubrovnik Gymnasium from 1870 to 1871.

As early as 1872, his persistent work ethic and perspicacity led him to the position of director of the gymnasium at Kotor. He would hold this post until 1877, when he resumed his teaching post at the Dubrovnik Gymnasium. Aside from a few short interruptions, he carried out his educational work in Dubrovnik until 1901. From 1894 to 1896, he was the Director of the Teaching School in Zadar. In addition to his teaching work, he accepted the position of school inspector in Bosnia, which he held from 1890 to 1893.

Despite all the aforementioned obligations, Luko became involved in the heated political and literary life of Dubrovnik at the time. It was during the period of his political maturation that the ideas bolstered by Vuk Karadžić’s fictitious ideology concerning the existence of an overarching Serbian Štokavian language spread through the Balkans. Perhaps it should not be surprising that it was in Dubrovnik, where the Croatian National Revival of the Dalmatian province shone the brightest not long before then, that these ideas were accepted in certain intellectual circles.

Namely, the somewhat mythologized memory of the period before the Austrian rule led to association with the ideas promoted by the Principality of Serbia, which was in the process of liberating its territory from the Ottoman rule. Unlike the rest of Dalmatia, there was no significant Orthodox minority in Dubrovnik, thus the idea was presented that Dubrovnik residents were in fact Serbs of Catholic persuasion. Luko Zore was one of the main representatives of Catholic Serbs in Dubrovnik.

Catholic Serbs presented their political opinions in the Slovinac journal, which was de jure a literary-critical journal. Following its closure, the role of Slovinac was succeeded by a new journal, Srđ. Luko Zore was the editor of Slovinac from 1877 to 1884. After Antun Fabris started Srđ in 1902, Luko Zore became its first editor. In that very same year, Srđ published the controversial poem Bokeška noć (`The Night of the Bay of Kotor’). The poem’s release earned Fabris, Zore, as well as Uroš Trojanović, the poem’s author, a prison sentence of two months.

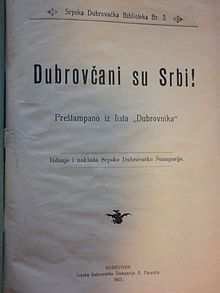

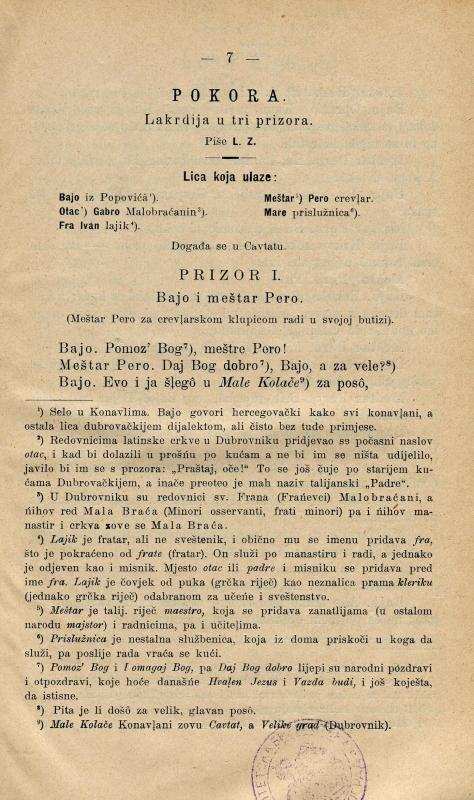

Although Luko Zore was one of the leading figures of the Serb-Catholic Movement in Dubrovnik, he remained a member of the People’s Party until the end of his life, even after the party changed its name to the Croatian People’s Party. At the persuasion of the Pucić brothers and other champions of the movement, he ran for the Dalmatian Parliament in 1883 and was elected representative. In 1897, Luko became a member of the Imperial Council in Vienna. Despite a successful political career, he often came into conflict with the authorities due to anti-state acts. Some of the most significant examples of this were certainly the poem Objavljenje (`Apparition’), which criticizes the society of the time, the poem Pokora (`Penance’), which depicts life in Cavtat in the 19th century, as well as the controversial article Dubrovčani su Srbi (`Dubrovnikans Are Serbs’). In order to minimize conflicts with the authorities, Luko often signed his works with either his own initials or the pseudonym `Milivoj Strahinić’.

In addition to teaching and political work, Luko Zore was involved in philology and literary research. He was particularly engaged in the study of the works of Čubranović and Gundulić. One of his more famous literary articles is Naš jezik tijekom naše književnosti u Dubrovniku (`Our Language Throughout the Literary History of Dubrovnik’), an early article in which he focused on the analysis of loanwords.

Zore was a multifaceted individual: a respected teacher, a staunchly opinionated politician, and a tireless cultural worker. He spent the last years of his life in Montenegro, where he served as Prince Nikola’s private tutor from 1901. Nevertheless, Luko could not truly distance himself from his native land, which can be seen most in his dedication in editing the Srđ journal. Srđ provided a renewed impetus to his later work, which in turn resulted in the publishing of the most radical articles of his career. Despite his tirelessness and constant desire to write, Luko Zore passed away at the age of 61 in Cetinje on 9th December 1906. The significance of his role in the cultural life of Dubrovnik was best evidenced by the fact that Srđ continued to be published for only two more years with various difficulties, until it was finally discontinued in 1908.