In the second half of the 19th century, the entirety of Europe became overwhelmingly interested in textiles. Even earlier than that, the textile industry was accommodating the basic needs of the bourgeoisie for textiles via a faster and cheaper production in large quantities. Hand weaving and knitting remained confined to rural areas and art studios.

As early as the very beginning of the 19th century, the modern inspirations for textile pattern designs became exhausted and the European public’s attention turned to folk textile clothing. Therefore, the patterns used in the manufacturing of industrial products were sought in rural motifs. An insight into the wealth of local handicrafts throughout Europe brought into focus the communities which had preserved their respective handicraft traditions due to the fact that they were located far outside the metropolitan areas. These areas were thus frequented by middlemen and traders, who would purchase original pieces of clothing for a pittance and take them away to other countries. In one of her public speeches, motivated by the strong commercial interest in the Konavle folk costumes and embroidery, Jelka Miš, a local schoolteacher from the time period in question, expressed her fear that valuable folk clothing would be taken out of the country and that, as a result, the future generations of locals would become unfamiliar with the handiwork of their native region. Her concern was brought on by the fact that the Konavle women were selling the folk costume clothing items of which they no longer had use for small amounts of money.

The interest in textiles also became an important aspect of education in the 19th century. Namely, handicraft was included in the school curriculum as a stand-alone subject. In addition to teaching, the task of the teachers, equipped with handicraft knowledge and techniques, was to collect and share new techniques, patterns, and methods of craftsmanship.

The aforementioned Jelka Miš was by far the most dedicated schoolteacher with regard to collecting all types of textile material in Konavle. The contemporaries of Jelka Miš who were also active in this regard were Nike Balarin and Paulina Bogdan Bijelić. However, their contributions were not as significant as those of Jelka. While Paulina’s commitment to heritage preservation began with her research on the Konavle embroidery, her greatest contribution to understanding the life and customs of Konavle was the writing and publishing of her findings on the subject. As for Nike Balarin, during her employment in Gruda, she collected an album of Konavle embroidery patterns, which was exhibited in Paris in 1900. Furthermore, she contributed several valuable texts concerning the Konavle customs to the Zbornik za narodni život i običaje južnih Slavena academic journal.

However, the scope of Jelka Miš’s work was not limited to Konavle. She collected samples from different regions, regardless of whether work or leisure brought her to those areas. Therefore, her sample books comprised of samples from various parts of the Balkans – northern Croatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, and Macedonia. Considering the truly impressive wealth of folk costumes and handicrafts of the aforementioned areas, her sample books have come to represent a veritable encyclopedia of embroidery techniques. She showed no interest in the intangible heritage interwoven with the embroidered fabric of the folk costume; her sole focus was the technique, i.e. the performance.

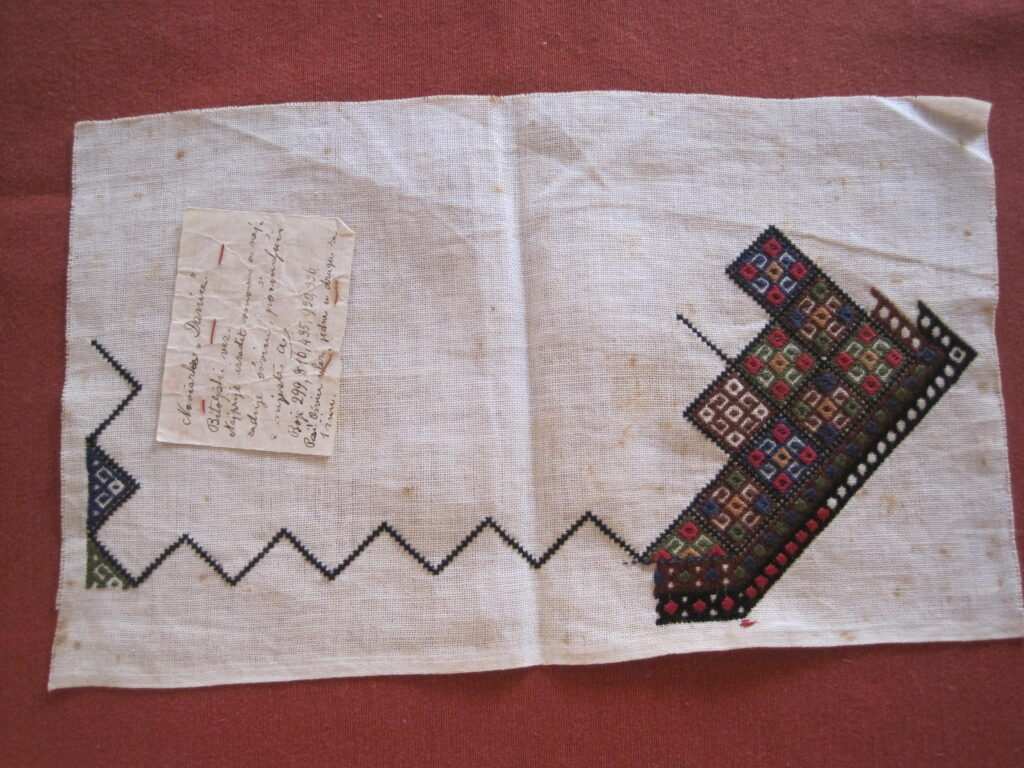

She collected the samples by replicating and/or drawing them in order to craft the initial elements of an embroidery pattern. Depending on the techniques used, certain patterns, such as the cross-stitch embroidery ones, allowed only drawing, while others could only be replicated by embroidering. She categorized the sample books which she made based on the geographical area of origin of the collected samples. Therefore, the names of the sample books are Sjeverna Dalmacija (`Northern Dalmatia’), Konavle, Hercegovina (`Herzegovina’), etc. Not only have these samples been kept as museum artefacts and documentation of cultural property, but they have also served as inspiration for the production of various homemade items, which has been developing as a craft since the beginning of the 20th century.

The influx of foreign textile patterns into Croatia, a country rich with its own handicrafts, was such that Salomon Berger, a prominent Croatian industrialist and textile trader of the time, warned of its negative impact on the country’s traditional embroidery. Namely, Berger feared that importing ready-made patterns would lead to the internationalization of embroidery, thus resulting in the loss of traditional Croatian forms and techniques. Therefore, he deemed it necessary to encourage `the wealthy to use regional folk patterns in decorating their homes. Jelka Miš already owned a large collection of her own and an organized association which produced, in Berger’s words, `clothing for the wealthy‘.

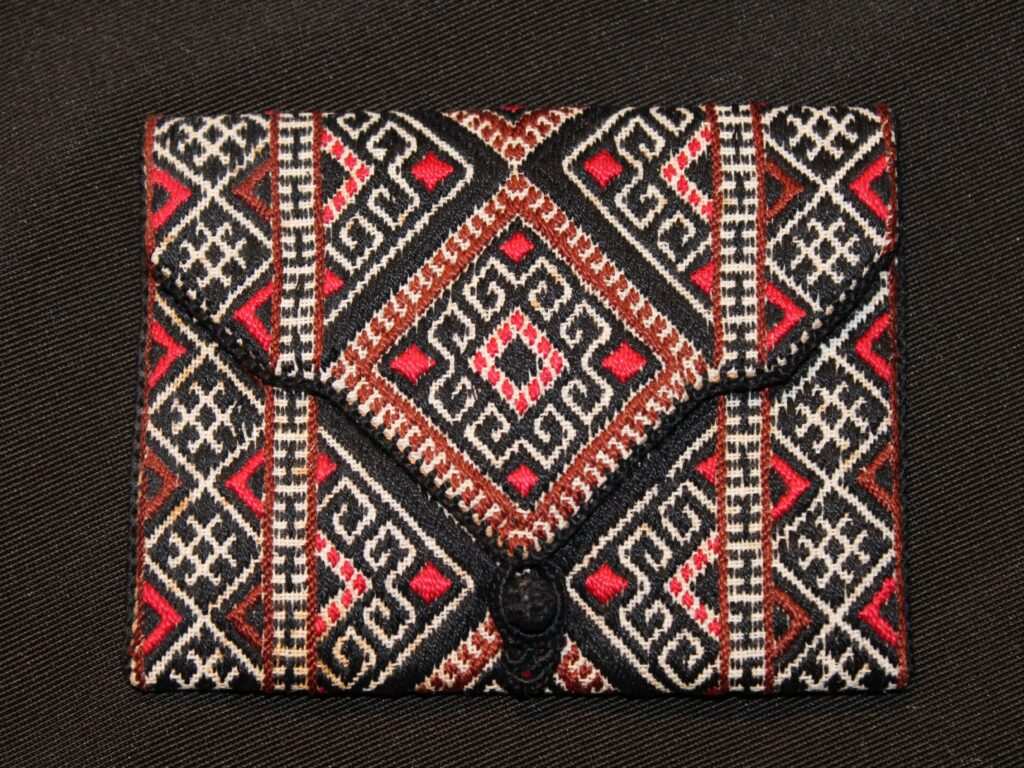

The production of such items required samples and a skilled craftswoman who could design them. The patterns taken from original folk costumes were shaped as required by the garments’ designs. They had to be adapted and redesigned for further use and production of high-value items. Matters such as the orientation the embroidery pattern, the appropriate number of certain decorations, and the compatibility of different patterns were considered of no concern. The only important concern was to fit the pattern into the new item, i.e. to redesign it in such a way that it retains all the basic features.

In addition to her technical competence and knowledge of embroidery techniques, Jelka Miš was filled with immense creative energy which allowed her to constantly create new customized patterns and combine them into valuable everyday objects or clothing items. She admired the folk motifs, but was angered by the ease with which the peasant women made mistakes while embroidering. With small stitches, the counted thread embroidery mistakes were negligible to the naked eye. However, both the redesign process and the process of crafting practical items required maximum quality performance from the embroiderer. Therefore, Jelka Miš’s samples are impeccable in terms of neatness and technique due to her corrections. As such, her samples do not provide a proper insight into the embroiderers’ relationship to their clothing, as well as into other values of embroidered items of folk clothing – the apotropaic marks, various semantic aspects, etc.

Under her supervision, the embroidery associations produced tablecloths, various sets, decorative pillows, wallets, dust jackets, needle cases, bookmarks, even children’s dresses. All these items were decorated using some of the techniques of a wider geographical area. Their high aesthetic value allowed them to promote the folk costume in the most dignified way and enabled the preservation of the traditional patterns even after the folk costumes were no longer worn in their respective areas of origin.

The production of the aforementioned items was organized in such a way that each part of each item was assigned a specific combination of patterns. Jelka or another craftswoman working as her substitute would start the embroidering process by delineating the main composition of the pattern and the selection of all elements. The girls who were better embroiderers would subsequently acquire the necessary materials and continue the initiated process.

Jelka’s patterns were replicated and almost every girl who attended her school had her own set of sample books, although these consisted mostly of Konavle embroidery and a few other types of traditional embroidery. It should be noted that during the 20th century, ošve (embroidered strips) and ogrovi (collars made of embroidered strips) belonging to other geographical areas entered the Konavle chestpieces from these catalogues. If the girls liked a pattern, they would integrate it into a chestpiece while embroidering their clothes. Even after the making of the Konavle chestpieces and sleeves was discontinued, the Konavle women continued embroidering for house decoration, for personal needs, and also in order to generate additional income via tourism.