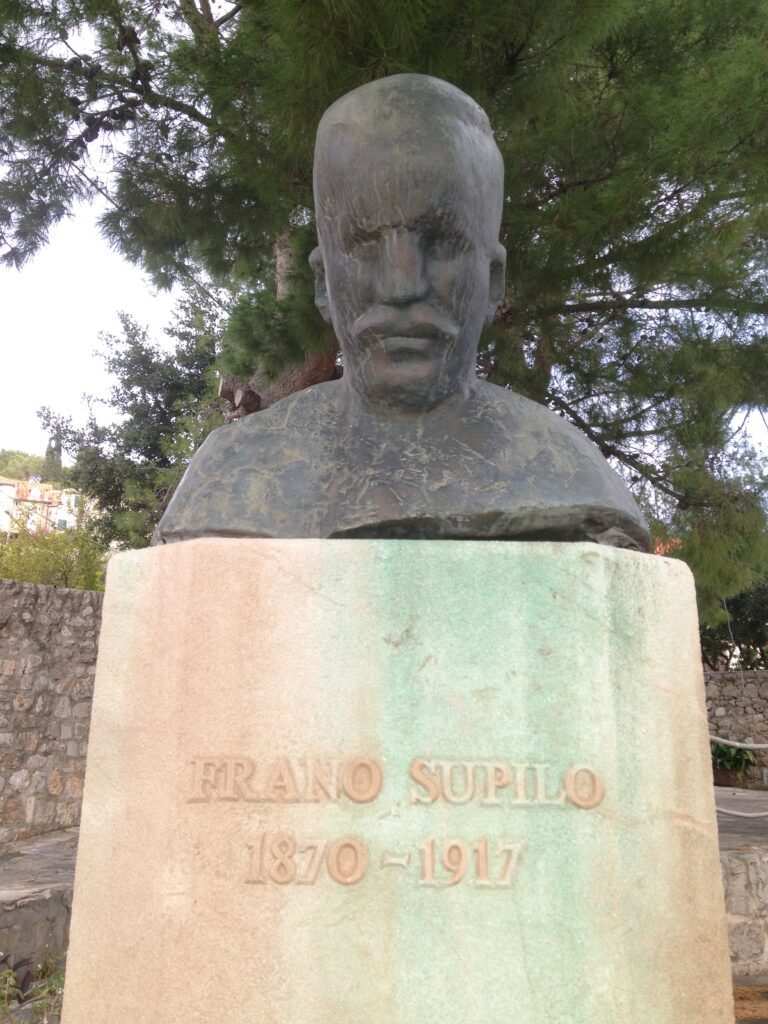

Unjustifiably neglected in recent Croatian political history, the great Frano Supilo is a tragic figure in Croatian politics. Born into a poor working-class family in Cavtat on 30th November 1870, he showed an interest in books and learning since his early school days. Supilo spent the first ten years of his life in Cavtat and then moved with his family to Dubrovnik, where he finished elementary and civic school. He subsequently enrolled in a nautical school, but was forced to stop his education due to his family’s financial constraints and lack of scholarship opportunity. In 1887, a two-year agricultural school was opened in Gruž, and Supilo, having received a scholarship, graduated from the school as the best student and was given the position of prefect (supervisor and teacher of students) in that institution.

Despite his modest formal education due to his family’s financial circumstances, Supilo worked diligently on his self-education, reading fiction, scientific papers and learning foreign languages.

In his article, Memories of Supilo, Antun Krespi wrote: `In Dubrovnik he learned Italian, German and French, all by himself! … He never frequented bars or taverns; he wasn’t a smoker, a card player, a womanizer, or a drinker; moreover, he was neither a hunter nor a fisherman.‘

Supilo became interested in everyday political affairs as a boy. During the visit of Rudolf, crown prince of Austria, to Dubrovnik in 1885, Supilo, along with a few friends, including Melko Čingrija, the son of Mayor Pero Čingrija, refused to take off his hat when the crown prince passed near him; this resulted in him and his friends being temporarily expelled from school. At the hearing following the “incident” in question, the fifteen-year-old Supilo answered one of the questions in the following manner: `We swore that we would always be Croats and that our work in the literary domain would be dedicated to this principle.‘

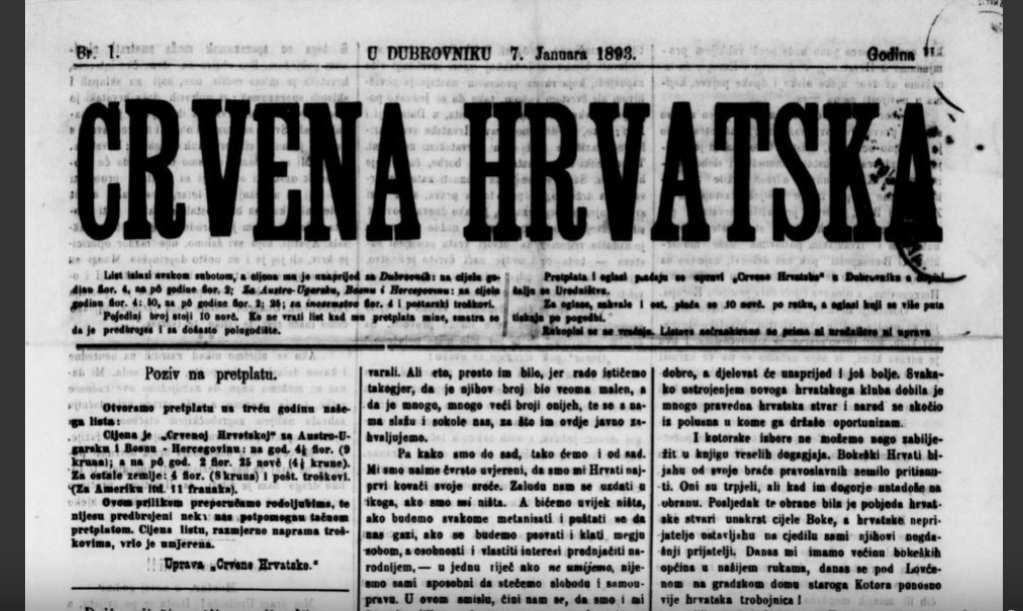

In the complex political landscape of Dubrovnik of that period, realizing that the People’s Party did not intend to take the initiative of uniting Dalmatia and Banska Hrvatska and that the coalition of the Italian-oriented Autonomist Party and the Serbian Party was growing stronger, young Supilo saw the Croatian Party of Rights as the only progressive political current at the time. At the age of twenty, he became the editor of the newly founded newspaper Crvena Hrvatska, whose goal was to highlight Dubrovnik’s Croatian roots and fight against the autonomist and Serbo-Catholic ideas.

At the end of the 19th century, Supilo moved to Rijeka (Sušak) and began editing the Novi list newspaper in 1900. Supilo’s dedication to his own work was marked by exceptional clarity and perseverance, interest in politics and almost statesman-like reasoning. The turning point in Supilo’s political activity was the so-called policy of the “New Course”, a political perspective held by certain Croatian and Serbian politicians from Dalmatia and Banska Hrvatska. It was motivated by the German pretensions of territorial expansion toward Eastern Europe (Drang nach Osten); consequently, its goal was the unification of the Croatian territories and the improvement of Croatia’s position within the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, with future aspirations of creating a new South Slavic state.

Connecting with the Hungarian opposition and supporting their struggle for independence, the Rijeka Resolution was signed, which was followed a few weeks later by the Zadar Resolution. Everything was prepared for the establishment of the Croatian-Serbian Coalition, led by Supilo himself. The coalition in question won a majority in the 1906 elections. However, a rift soon arose between the New Course proponents and the Hungarian opposition due to the adoption of the so-called Railway Pragmatics, which was aimed at establishing Hungarian as the sole official language on the railways in Croatia.

The behind-the-scenes political games of the Austro-Hungarian authorities preparing the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a high treason trial against 53 members of the Serbian Independent Party was held as a response to the success of the Croatian-Serbian coalition. They were accused of cooperating with the Serbian authorities with the aim of overthrowing the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. At the same time, Austrian historian Heinrich Friedjung published an article in the Neue Freie Presse newspaper accusing Frano Supilo of being an agent of the Serbian government. Supilo in turn filed a defamation lawsuit in the so-called Friedjung trial, in which he succeeded in proving that Friedjung used forged documents provided to him by high-ranking state officials. One of the witnesses at the trial in question was the Czechoslovak politician Tomáš Masaryk.

Disagreeing with the policy of Svetozar Pribičević, Supilo left the coalition and emigrated at the beginning of the First World War, first to Italy and later to England. Supilo was very often mentioned in the novels, essays and writings of the Croatian writer Miroslav Krleža, who presented him as a sort of a model moral figure in politics, but also as his own personal political role model.

Frano Supilo, alone and abandoned, ravaged by a serious illness, passed away at the age of 46 in a mental hospital in London on 25th September 1917.