From the Facebook page Zbirka Baltazara Bogišića HAZU u Cavtatu

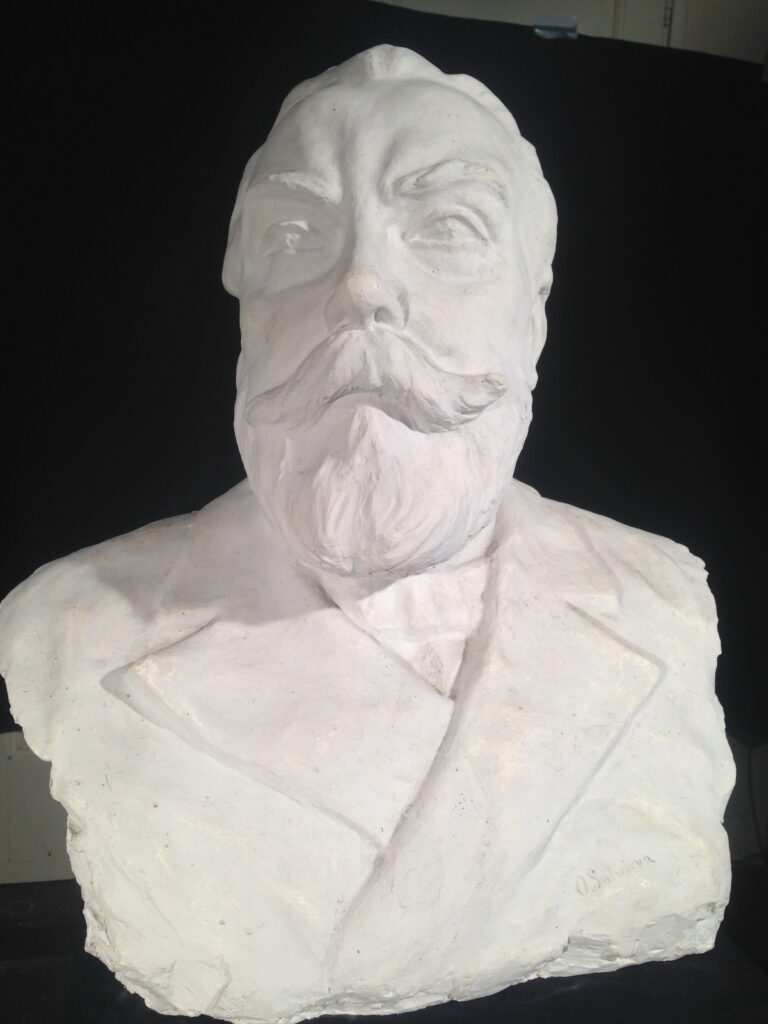

`If some of the folk economics experts did not hesitate to adhere to the saying “The freedom of every nation can be measured by its wealth, and its wealth can, in turn, be measured by its freedom” as their guiding principle, even though such a principle is not without its exceptions, it could not be held against us if we were to say that a nation’s level of education can be measured by its wealth of intellectual property contained in books.‘This passage was written in 1866 by Baltazar Bogišić in one of his museological studies. A Cavtat native born on 20th December 1834, Bogišić was a man of such extensive knowledge in a variety of fields that it would not be an exaggeration to place him among the greatest minds in the European science of the 19th century.

Having received his primary education in Cavtat, Bogišić was engaged in a prosperous family business due to his father Vlaho’s reluctance to further his son’s education. Following Vlaho’s sudden death, Bogišić departed for Venice in 1858, where, by virtue of his interest in learning, he passed his gymnasium exam the very next year; he subsequently enrolled in the University of Vienna’s School of Law. A man of wide interests, Bogišić simultaneously attended lectures in history, philosophy, and philology at the universities of Berlin, Paris, Munich, Giessen, and Heidelberg. He obtained a doctorate in philosophy in Giessen in 1862 and a doctorate in law two years later in Vienna. He received his first employment in the Vienna Imperial Court Library in 1863 and remained there for five years as a librarian in the Slavic department.

At the time, Vienna was among the most significant centres of European science, and for Bogišić it was meeting point for many prominent scientists and provided opportunities for making important acquaintances. He was interested in the history of the South Slavic peoples, and especially Slavic customary law. He would work for two years in the service of the Ministry of Defense, initially as a school advisor in Timișoara and Petrovaradin, and later in Vienna as a member of a panel formed in order to reorganize the educational system in the Military Frontier region. Near the end of 1869, Bogišić accepted the invitation to teach at the Department of Comparative History of the Rights of Slavic Peoples in Odessa, where he remained for three years.

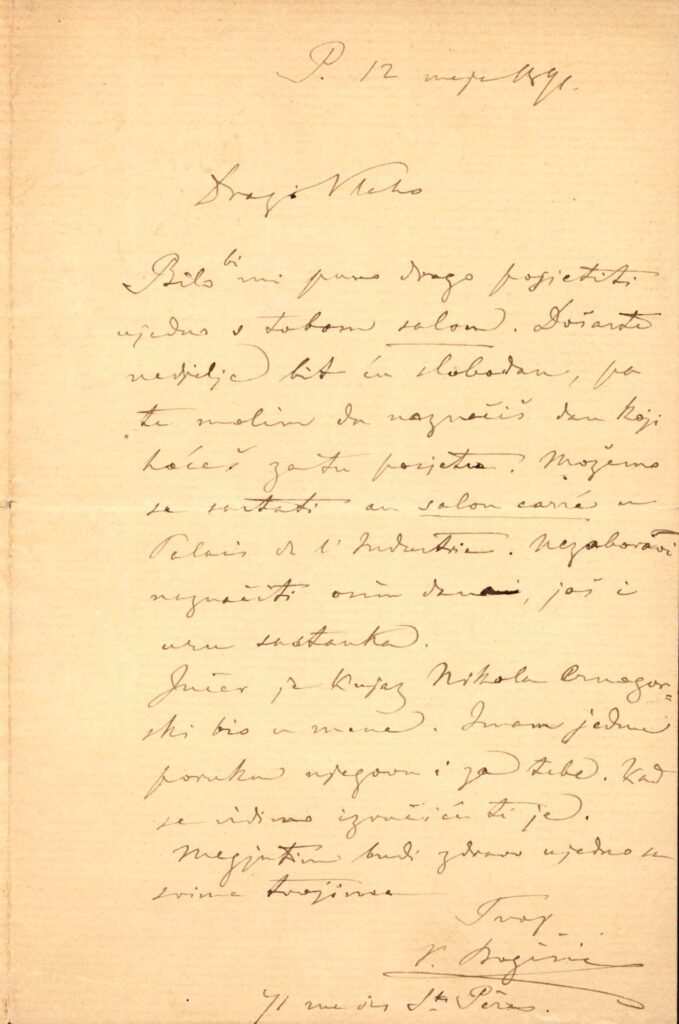

What followed was arguably Bogišić’s crowning achievement – the drafting of the General Property Code for the Principality of Montenegro. The codification process lasted intensively for 15 years. The Code itself, as well as its drafting process, attracted great interest from the professional and scientific public. The Pravo journal reported that the Montenegrin duke Nikola was extremely pleased with Bogišić’s work on the drafting of the Code and in return spoke highly of it in a conversation with the Austrian emperor in Vienna.

Moreover, a news article from 1879 in the aforementioned journal mentions the Japanese Minister of Finance who, upon his visit to the World Exhibition in Paris, requested a meeting with Baltazar Bogišić to inquire about certain issues related to the codification of Japanese law.

As a follower of the historical school of law, founded by the German lawyer Friedrich Karl von Savigny, Bogišić regarded historical practices of a community manifested in folk customs as a source of law. As such, he deemed them important for both study and practical application.

He wrote: `… the people do not ask legal scholars about the law which they create themselves, just as they do not ask philologists about the language they speak. Therefore, in addition to law and legal science, it is worth researching customary law, both in its current and previous forms, since it contains many remnants of the legal institutions of old.‘

It was on these foundations that Bogišić built the Montenegrin Property Code, legitimizing people’s law while simultaneously adapting it to the needs of a modern society. The Code was issued by the decree of Duke Nikola and entered into force in 1888. Bogišić devoted himself to further scientific work and travels, but at the repeated requests of Prince Nikola, he accepted the position of Montenegrin Minister of Justice in order to oversee the application of the new code.

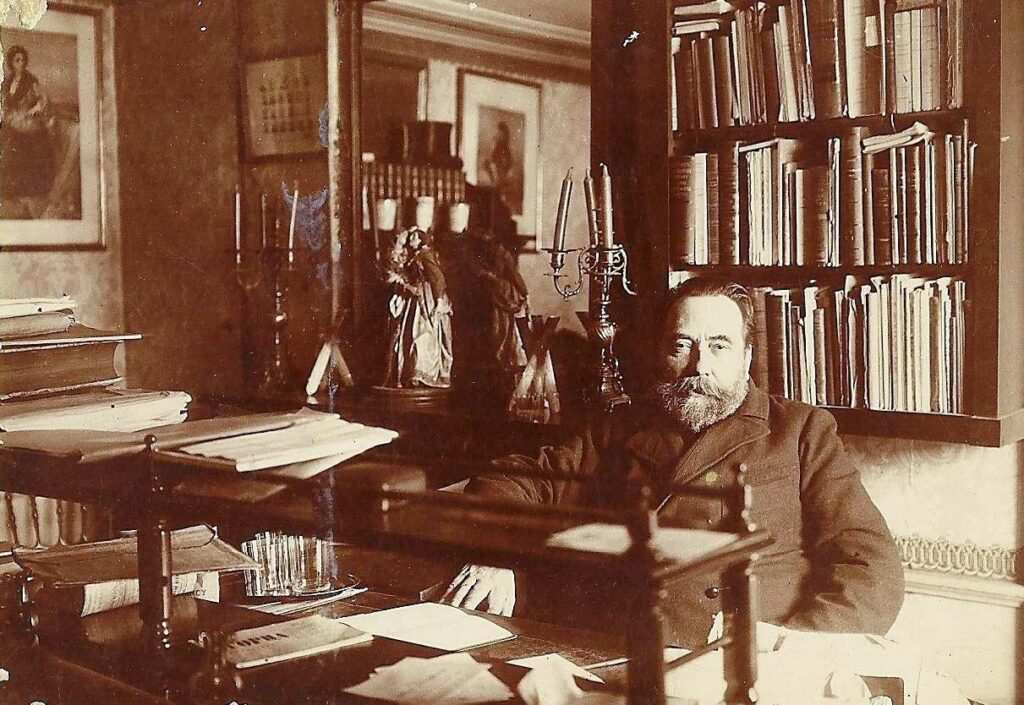

Following his well-deserved retirement in 1899, Bogišić lived mainly in Paris. A lawyer, historian of law, ethnographer, collector, traveler – in short, an erudite man in the true sense of the word – he was a member of several European academies and spoke seven languages. His truly rich and diverse scientific and cultural activity is today kept in the the Baltazar Bogišić Collection, founded by the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts and located in Bogišić’s own home, in Cavtat.

Suffering from failing health, Baltazar Bogišić passed away in Rijeka while traveling to his native Cavtat on 24th April 1908.