The summer season in the traditional culture, unlike the winter period, was not as rich in terms of calendar customs and folk festivities; only localised smaller-scale events were held during that time of the year, as well as the occasional feast days dictated by the liturgical year. Summer was the season during which no significant life events that could be scheduled deliberately, such as weddings, took place. The reasons for that lie in the very structure of the traditional society, i.e., in the lifestyle typical of rural areas such as Konavle.

Until recently, the locals have lived in large households or household cooperatives (‘zadružne obitelji’) that the families consisted of up to ten or even more members spanning three or more generations. Such families were worker’s communities in which a large household and its agricultural property required everyday effort to be maintained. Despite no shortage of workload even during summer, the household members would adapt to the immense seasonal heat that determined the summer rhythm.

The typical summer day would start at dawn, when the household members would start working. The feeding of the farm animals, the first chore of the day, preceded breakfast. The young girls would then bring bundles of branches required for cooking to the kitchen, while the housewife would start preparing coffee. After drinking barley coffee roasted in tamburić, a specialised coffee roasting container, the younger household members would depart for work on land, while the elders and the housewife would stay at home. The housewife’s primary task was preparing lunch for the numerous family members. The cooking was done over an open fire in an enclosed room in which extremely high temperatures were reached during summertime. In the early 20th century, the Konavle women started using wood cook stoves in the kitchen(regionally known as komin), most commonly roofed by a reinforced concrete slab.

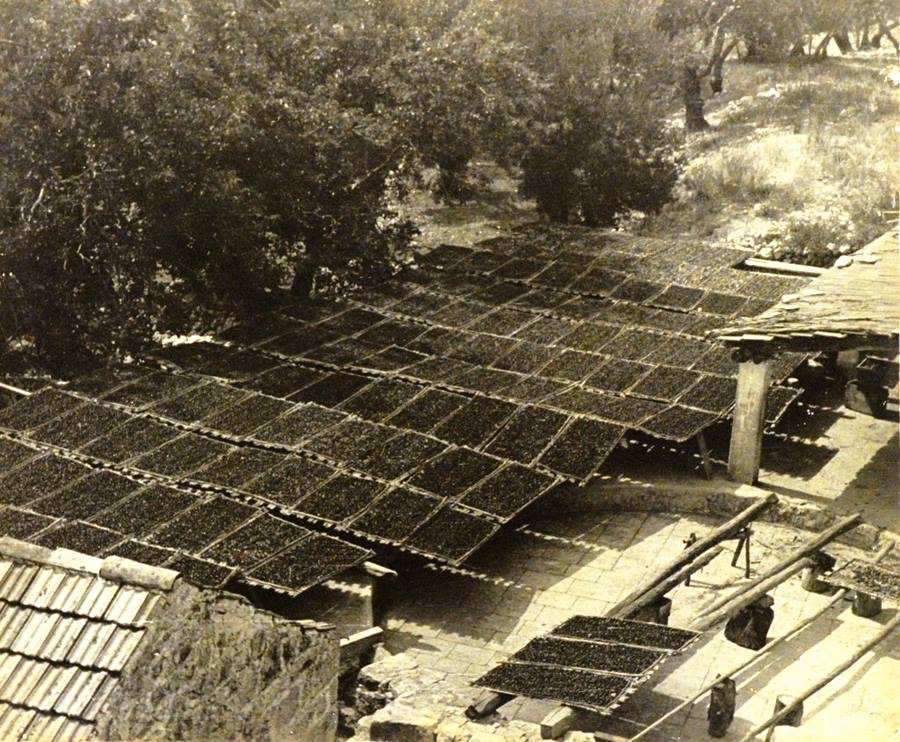

The housewives would spend their days in the extremely hot kitchens preparing meals to be served to other family members. The remaining women’s chores were distributed among the younger girls and women in accordance with the predetermined workload distribution: ‘Everyone knew who was supposed to sweep which terrace, who washes the men’s shirts, as well as who washes the children’s shirts.’ The women had to sweep the terraces and cattle pens as if they belonged to a palace or castle on daily basisin order toprevent infestations caused by barn insects ‘cause summer is a season when insects breed, and woe betide you if some manage to nest somewhere inside or near your house! The women would make tomato sauce in shallow bowls on the terraces in order for the tomatoes to be pasteurised by the heat of the summer sun; they would leave the tomatoes in the bowls and occasionally stir the resulting sauce. Furthermore, the benefits of the sun were exploited for drying figs to be used as a winter snack. The figs would be laid out across jese – pads made of reed and also used in the process of silkworm rearing in springtime; the figs had to be occasionally turned while being exposed to the sun in order to be dried from all sides.

At dawn, older children would lead the cattle to pasture and would return it home in the early evening; the cattle were kept in pens and barns in the immediate vicinity of houses, while mobile enclosures were also employed in the mountainous region. Younger women and men would go to vegetable plots and orchards so as to dig the soil, reap the crops, pick vegetables and fruits, work on grapevine, harvest potatoes, gather hay and perform numerous other agricultural chores. The goal was to accomplish as many tasks in the early morning hours before the sun rose fully, at which point they would return home for lunch. The lunch was served promptly at noon. They would drink fresh water obtained from gustijerne – rainwater cisterns carved in stone. The water, as well as the refreshing bevanda (a mixture of wine and water), were drunk from copper-made romjenče (buckets used for storing drinking water). Following that, they resisted fatigue and gathered strength for the afternoon’s work on vegetable plots and a busy early evening.

While the summer sun would burn bright in the early afternoon and the immense heat pervaded the air, an immaculate silence would descend upon the villages. The adults would retreat to their bedrooms and rest, while the children would play quietly in secluded corners of the terraces or cattle pens. They were afraid of rogato podne, a folklore monster which would abduct them should they make noise. The early afternoon’s silence was broken only by the joyful murmur of the adolescents, who were resting under the mulberry trees in front of the houses, as well as by the cricket’s song heard in the distance. While the boys would craft tools and musical instruments, the girls would embroider. The “working pastime” had its joys.

The evening brought some much-needed fresh air, although much work still had to be done: the milk had to be curdled, the animals had to be fed, the eggs had to be gathered, men needed to be provided with water in order to wash themselves, dinner had to be prepared and served for everyone, and younger children had to be fed and tucked in. The summer nights are short and the sun rises quickly, thus a good night’s rest was in short supply. The youngsters would spend the summer nights sleeping on the terraces under the stars, running away from the houses’ hot walls; in the morning, everyone would restart the summer day’s routine.

Photographs were taken from the Facebook group Dubrovnik nekad.