Despite the common belief, the sole purpose of hunting is not killing wild animals for sustenance. In fact, the hunting is also concerned with wildlife nourishment and preserving biodiversity. In other words, the primary task of today’s hunters is to prevent the extinction of animal species or the endangerment of one species by another. To that end, the game is counted during close season so as to determine the number of the animals that must be culled.

According to all previous knowledge, hunting has been present since the earliest era of the humankind’s existence. Prior to the domestication of animals, it was the only means of adding meat to the humans’ diet. Various animal species required different hunting strategies due to their speed or strength superior to that of a human; this in turn contributed to the development of numerous hunting devices and methods. Some of the most common methods of hunting include: driving (prigon), group stalking (pogon), posting (doček) and calling (vabljenje). The hunting weapons used differed from one area to another, while the type of game also dictated the hunters’ choice of equipment. Consequently, the larger game animals were hunted using spears and traps, while the bow and arrow were used for hunting the smaller ones. Besides equipment, various animals were used to aid the hunters in pursuing prey; the most famous among them are dogs, of which there are numerous different breeds developed for various type of hunting. Falcons were also very popular animals used for hunting prey in the past, although falconry has been on the decline in recent times.

In order to fully grasp the significance of hunting, one should analyse the thoughts on hunting held by various civilisations of the past. In Roman law, although all citizens had the right to hunt, the game could be hunted only within the bounds of one’s private property. In the medieval period, a hunting ban was imposed upon all those who did not have the formal permission of the king, who was de jure owner of the entire country. The right to hunt was one of the regal rights (jure regalia) bequeathed by the king. This in turn often contributed to the rise of poaching due to the fact that the majority of the subjects was not permitted to hunt. The decline of feudalism brought changes to the rules of hunting. By the latter half of the 19th century, most European states had started devising their own respective game laws. Hunting today is allowed only to those who have a hunting licence and hunt in accordance with the issued laws and regulations.

Close season (lovostaj) is among the most significant hunting laws. The term in question refers to the period in the year when hunting of particular game is officially forbidden so as to allow for undisturbed game gestation and the subsequent raising of the young. Certain animal species are particularly endangered; thus, a permanent close season is provided for them. Conversely, species whose numbers threaten the sustainability of biodiversity can be hunted freely, with mothers leading the young and pregnant female specimens being the only exceptions to uninhibited hunting. In Croatia, such species include: fox, badger, mongoose, jackal and wild boar.

Much of what is known about hunting in Konavle has been retrieved not only from the 15th century accounts, but also from the bas-reliefs featured on the medieval tombstones(stećci) in the village Brotnice; nevertheless, the most is known about hunting in the 20th century. According to the accounts of narrators, the locals commonly started hunting as children, initially starting by using simple deadfall traps for hunting sparrows and young blackbirds: ‘Bird mating caused damage to the crops, so we would make deadfall traps and check if someone caught a bird before school every morning. We would make the traps by taking a somewhat flat stone and putting a small twig, as well as a morsel of bread as bait underneath it. When approaching to eat the bread, a bird would knock over the twig and get trapped under the stone.’

The Konavle residents were subsistence farmers and herders for centuries, therefore hunting was primarily oriented at protecting crops and farm animals. Nonetheless, much like in other parts of Croatia, the competitive spirit was always present in the local hunting activities. On a related note, the Croatian hunters have always exaggerated the quantity and quality of their spoils to such extent that the Croatian equivalent of the English idiom ‘cock-and-bull story’ is lovačke priče, literally translated as ‘hunting stories’. While various bird species were hunted in Konavle, especially in the Konavle Valley (Konavosko polje), the most hunted game were wild boars, who were the most troublesome garden and vineyard pests. In addition, rabbits, garden dormice and hedgehogs were also commonly hunted for the same reasons: ‘Dad would often catch a hedgehog and make a stew, which would chase mum away because she hated the smell.’

The recent times saw the emergence of jackal population; the narrators remember the jackals being chased by the locals due to their notoriety as pests. Foxes and goshawks were chased to the same extent; the hunters would carry the foxes they killed through their village. The narrators say: ‘When they’d catch a fox, they’d carry it through the village and shout ‘Look! A fox!’, and the women would in return gift them with eggs or oranges.’ Although few local residents remember the presence of wolfs in Konavle (with the exception of the Konavle Hills, where wolves from Herzegovina would sometimes migrate), certain 16th century records show that they were hunted out by the locals as well. According to the accounts of older residents of the Dubrovnik Littoral County, no wolves were sighted for some time after World War II ‘since they were poisoned, but the elders would tell stories about their wolf hunts’.

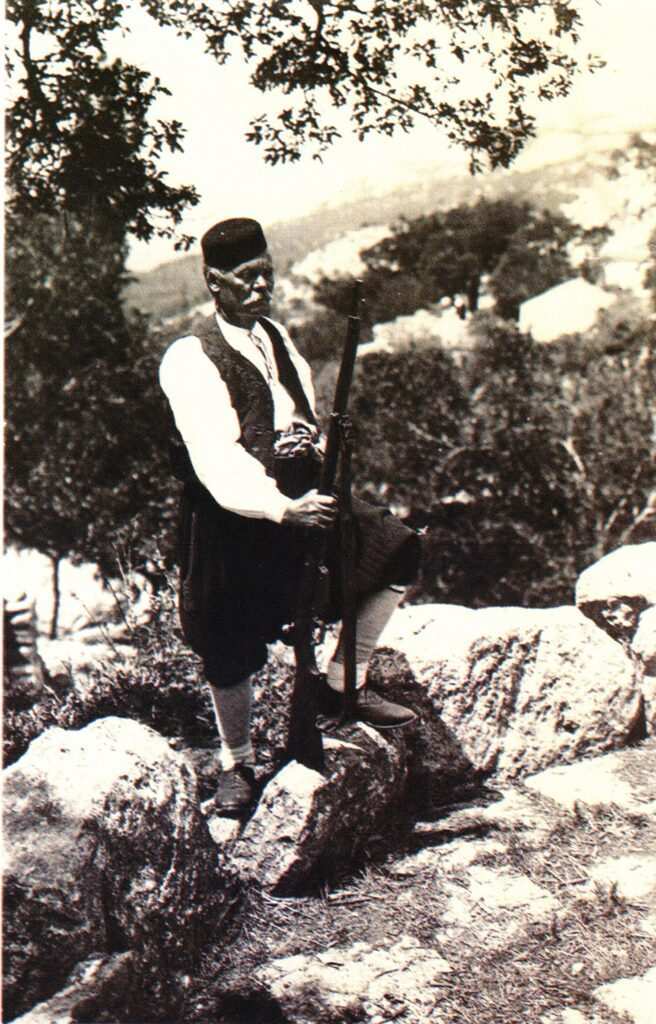

Besides preventing the growth of the animal populations which caused damage to the crops or farm animals, the locals also hunted in order to profit financially. The narrators from Duba Konavoska, a village in the mountainous region of Konavle, provide information on that matter: ‘One ermine’s fur would get you a calf.’ Unfortunately, this often led to poaching using iron traps (gožđa). Namely, the fur of ermine and fox was extremely profitable – it was sold to merchants who would resell it on the Italian market. The supervision of hunting activities in Konavle was made difficult due to the fact that many local residents had hidden the rifles that they had obtained in either of the World Wars, thus the hunting authorities could not easily identify poachers. Nevertheless, the formation of hunting associations, resulting in the gradual predominance of licenced hunters, partially contributed to the decline in poaching. Moreover, the narrators compare the state of weaponry used in the 20th century compared to the contemporary weapons: ‘Before the (Homeland) War, pretty much all hunters only had 12- or 16-gauge shotguns, while other rifles weren’t used. Nowadays, for instance, you can’t go big-game hunting unless you’ve got a carbine.’

Although hunters are present throughout the entirety of Konavle, Lovorno has become a synonym for a hunters’ village. As a consequence, jokes on the account of their hunting habits can often be heard: ‘Why are the people from Lovorno the only ones in Konavle to open doors with their left hand? – Because they hold a rifle in their right hand.’ Another example of the joke on their behalf is: ‘A man from Gruda said to another: ‘We should go hunting in the valley, the ducks have landed.’ The other man responds: ‘Even if the Virgin Mary herself landed, the Lovorno people would’ve shot her by now.’

On a somewhat related note, the narrators also say that hunters enjoyed certain privileges, ‘because no one would stop a hunter in their tracks and ask them where they were going, so you could go across the valley to meet your girl without anyone knowing about it.’ There must be plenty of other similar anecdotes, but those are probably best left to be told at some other time.