Along with the Art of Making Konavle Embroidery, which acquired the status of a protected intangible cultural good in 2015, Konavle is richer for another good, the Konavle wedding toast. Namely, back in 2017, the Museums and Galleries of Konavle submitted to the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia an application form for the protection of this cultural property. At the session of the Commission for Intangible Heritage in 2018, it was said that the toast has the status of a cultural good, which was confirmed by the Expert Commission of the Ministry at its session on 23 December 2020.

Although we are aware that protected status is worthless if there is no bearers and preservation of the good, this is a great confirmation of Konavle’s traditional culture. A confirmation of the centuries-old survival of the local dialect that provides a strong link between modernity and the oldest known corpus of Konavle’s traditional life. The toast was certainly performed centuries before it was first written, but ever since it was first written – to this day it has remained in the same corpus, as a toast that arouses admiration for its greatness and complexity. It was transmitted orally, and the tendency to make a written record was frequent throughout the 20th century.

In short, the Konavle wedding toast is a longer ceremonial speech always of the same shape and content that is used appropriately, drinking to health and well-being at weddings in Konavle. It is performed by a toastmaster in front of the wedding participants just before the main course at a wedding dinner or lunch. It consists of a corpus of speech in which the wholes are separated by the invocation of the toastmaster: As it will be, if God wills it! To which those present, standing on their feet, respond: Amen, God willing!

This is the only complete surviving toast in Konavle. Its parts are performedoften, and on other festive occasions. Family and village festivities pass with toasts extracted from the wedding toast corpus, as short expressions of wishes to persons or conditions, while in the field we witness only the entire toast corpus we know today at wedding festivities and partly at the family patron saint celebrations. For example, the toast from Konavle, which was published in 1935 (Yugoslav Printing House Dubrovnik), refers to toasting on a family patron saint name, and is identical to a wedding toast, except that the part that toasts to marital values is excluded from it. We rarely hear such a toast today.

Although the form of weddings in Konavle has changed in scope and content in the last 150 years, the toast has survived as the central part of the ceremony. It is still spoken today at all Konavle weddings and, as before, is the central toast in honour of all the festivities. Saying a toast culminates in wedding joy. We could say that we moved on to the second part of the wedding with a toast.

In all known forms, and in the distant past and today, it is held at the moment when the roast (main course, in poorer situations the only dish, and in richer ones the fourth sequence) is brought to the table, before the dish is approached (which until about the 1920s was announced by the song Let’s hit the roast (Udrimo na pečeno)).

By the middle of the 20th century, the toast would be introduced by lighting a candle on the table and praying for the deceased. Today the toastmaster calms down and raises the guests to their feet with his introduction. All wedding guests, or all participants in the wedding dinner or lunch listen and answer Amen, God willing for each completed unit.

Until the middle of the 20th century, almost all men in Konavle knew how to say a wedding toast in its entirety, so there was no wedding where someone would not know how to say a toast. Therefore, when the wedding guests gathered, there were no problems with saying wedding toast and toasts in honours. That speech lived in the fabric of Konavle people, and the drinking would begin spontaneously, but in order. The Stari Svat (respected older man), the First One (person leading the wedding procession), the Dolinbaša (one of the groom’s sons-in-law), the Groomsman – everyone would drink and toast. The Respected Older Man would rise during the roast and begin to address the sweet and dear brothers. It was not necessary for him to finish it, both the Best Man and the Host of the Table could continue. In the recent past, the whole toast is the speech of one toastmaster. The toast is followed by a toast with a bukara (toastmaster’s bottle) passing from one participant to the other: Healthy that you are my Respected Older Man, healthy that you are my Host! In Croatian: Zdrav da si mi stari svate, zdrav da si mi domaćine!

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, a toast, if none of the wedding guests were skilled, was performed by a toastmaster, often invited to a wedding just to perform a toast. Such a toastmaster, who is invited only for a toast, is given gift by the bride that is identical in shape to the gift for the Host of the Table. The address in the toast, although it is said about the marriage of two young people, is aimed at parents or hosts of the house. The bride who passes from one home to another is given a blessing in several places, while the groom is hardly mentioned. Invoking a blessing on the host is considered to be an indirect invocation of a blessing to the newlyweds.

The toast begins with addressing the participants as sweet and dear brothers, after which all aspects of life in which good is invoked are touched upon. After the structure is defined in the first part, God – we, there is a section on honesty and reputation, and customs as an unchangeable goal. The invocation of the blessing of agriculture, works, travel follows; then the invocation of abundance in food, property and health and joy, and the invocation of good that is comparable to natural elements and metaphorical descriptions from nature, then the invocation of the blessing of today’s joy and the blessing of the bride.

After the invocation of the blessing, the toast is drunk, in order: for God, for Jesus and the health and seed of the host, and the family order, for the Holy Trinity and community, for the sad and reluctant, the call for good and the last drink of the table and finally, for the host. As already mentioned, after each toast the participants loudly approve with the words Amen God willing! Performed for more than 150 years, and recorded in writing for the last 100 years. The toast being printed provided an understanding and insight into the traditional rite that has largely disappeared in the newer way of life.

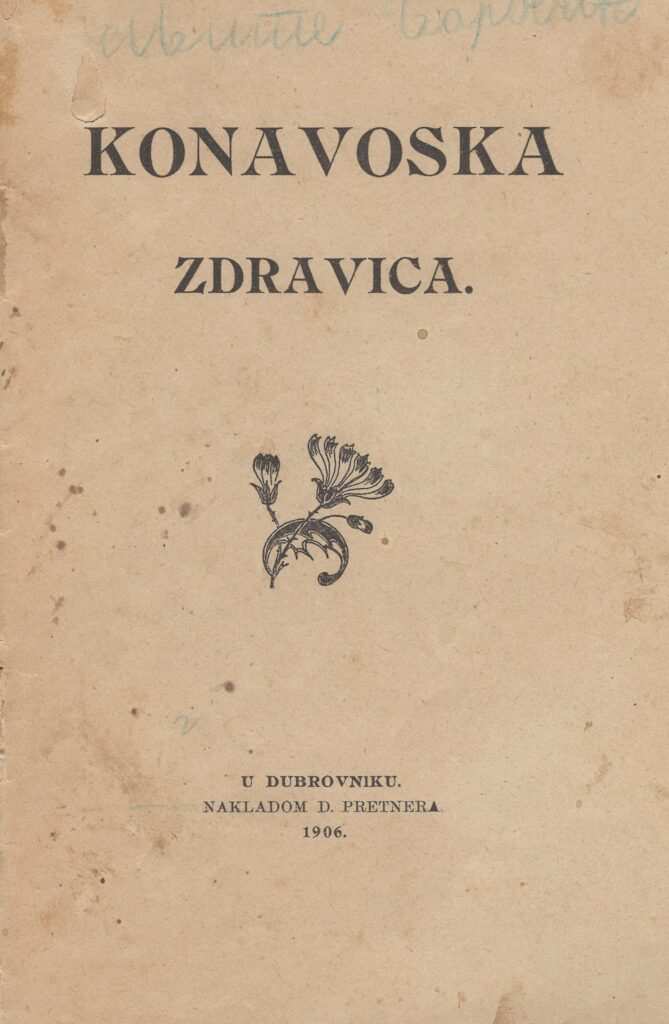

First wedding toast was printed in Dubrovnik in 1886 by the Pretner printing house, and towards the end of the century Antun Radić transmitted its fame with the help of Nika Balarin, announcing its popularity and identical structure at the time. The Konavle toast has been described as a distinctive example of rhetoric and the ability to use language for complex forms of expression in a rural setting. However, Radić was wrong when he did not predict a good future for it, thinking that it could not improve, so would therefore soon disappear. It was recorded and published several times during the 20th century, and we find it in manuscript form in many houses in Konavle.

We in Konavle are proud of our bearers of the Konavle toast, their dedication and love for this intangible good. Each of them has its own story and its own reason for being a toastmaster today. They perform not only for the needs of folklore, but as true advocates of good wishes at the weddings of newlyweds, carrying in their speech all the power of the past, which due to its values is still a source of best wishes and protection. Thanks to them, Konavle’s traditional culture in this form received the national status of a cultural good, and thus undoubtedly greater presentation and maintenance.