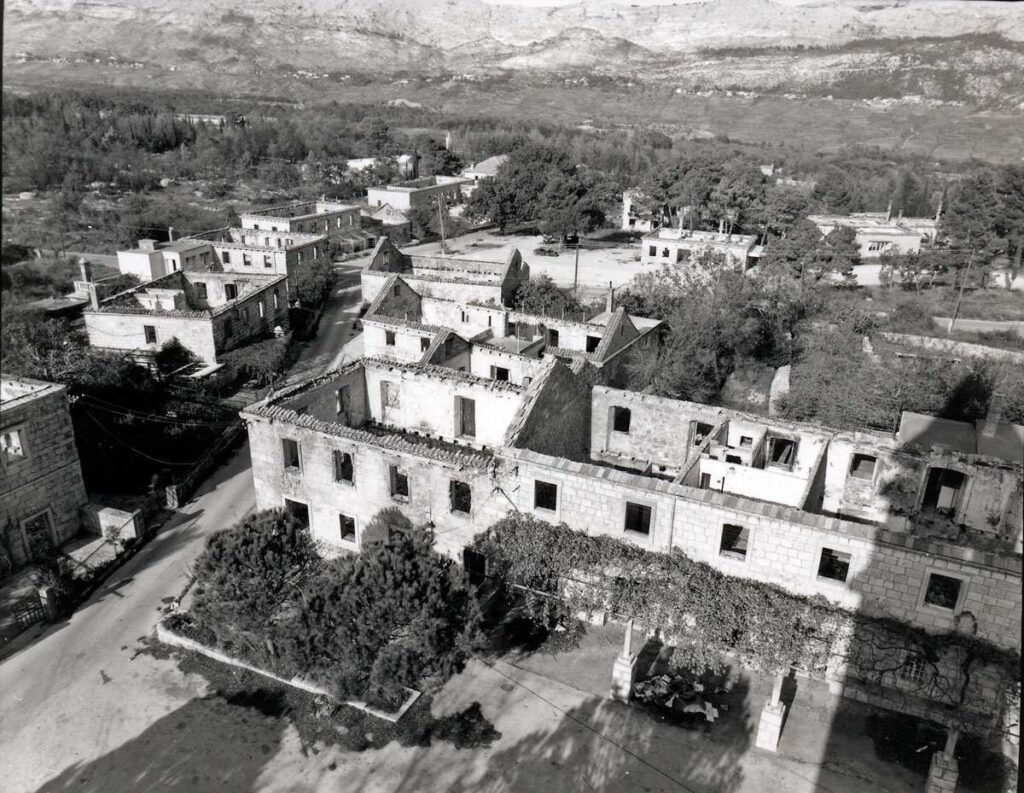

Aerial view of war-torn and burned area

Photo credit: Goran Les, November 1992

When the fall of the Berlin Wall began on November 9, 1989, the demolition of the ideology that had ruled eastern Europe since the end of World War II was hinted at. At the very heart of the communist government in the USSR, already by the mid-1980s, talk of change was instigated by Perestroika and Glasnost. On the other hand, the former SFRY has been in a deep crisis since 1980, when the lifelong president and dictator Josip Broz Tito died, whose personality was almost the only connective tissue of the people and the nation of the state.

In addition to the political crisis that the rulers sought to resolve by establishing the President of the Presidency and continuing the cult of personality of the late president, the country was hit by a severe economic crisis, domestic currency inflation, oil shortages and an increase in smuggling activity. The situation was further complicated when the SANU Memorandum was published in 1986, which spoke of the endangerment of Serbs in all republics and autonomous provinces, and in fact revived the idea of a Greater Serbia from the 19th century. The signatories of the Memorandum only needed a politician who would implement the idea, and they found it in Slobodan Milošević.

The radicalisation of the Serbian nationalistic idea gained a foothold in Serbia, Montenegro, Vojvodina and Kosovo in 1990 where at the first multi-party elections, Milošević’s candidates won seats while in the republics, democratic option were victorious. That same year in Croatia saw the start of the open revolt of Croatian citizens of Serbian nationality known as the Balvan Revolution. Police suppression of the uprising was prevented by the Yugoslav National Army (JNA), which for almost a year created a buffer between the Croatian police and the insurgent Serbs, and in fact, helped spread the uprising.

A resolution to the crisis was sought by way of referendum on independence which took place on May 19, 1991 and was based on self-determination from the 1974 constitution. Despite a voter turnout of over 80%, of which more than 90% were in favour of independence, the European Community in an attempt to resolve the rift peacefully, agreed on a three-month moratorium between Slovenia and Croatia on one side and Yugoslavia on the other from the 7th of July. In that three-month period, the aggression against Croatia by the JNA helped by insurgent Serbs and paramilitary forces, began.

Unlike other border parts of the Republic of Croatia, there was no internal Serb uprising in the area from Konavle to the Neretva Valley, so the authorities in Serbia and Montenegro tried to justify the need for aggression by using propaganda that 30,000 Ustashas were preparing an attack on Montenegro. Another specificity of the Municipality of Dubrovnik, under which Konavle was also, is that it was the only demilitarized area in the former state. Namely, back in 1971, due to tourism, it was decided that the area of Dubrovnik must be demilitarized, and the weapons of the Territorial Defence were transferred to Duža near Trebinje. In other words, there was no stockpile of weapons in the entire municipality to organize defence, except for police and privately owned weapons.

On the other hand, in the area of the municipality there were two military facilities, a resort in Kupari and the polygon of the technical-experimental centre on Prevlaka. The defenders of the Municipality of Dubrovnik had about 1,300 people with arms, i.e. 700-800 members of the National Guard and 500 members of the police. In addition to light small arms, there were three 120mm mortars, two 85mm cannons and four 75mm cannons in the entire area of the municipality, but only one had target devices.

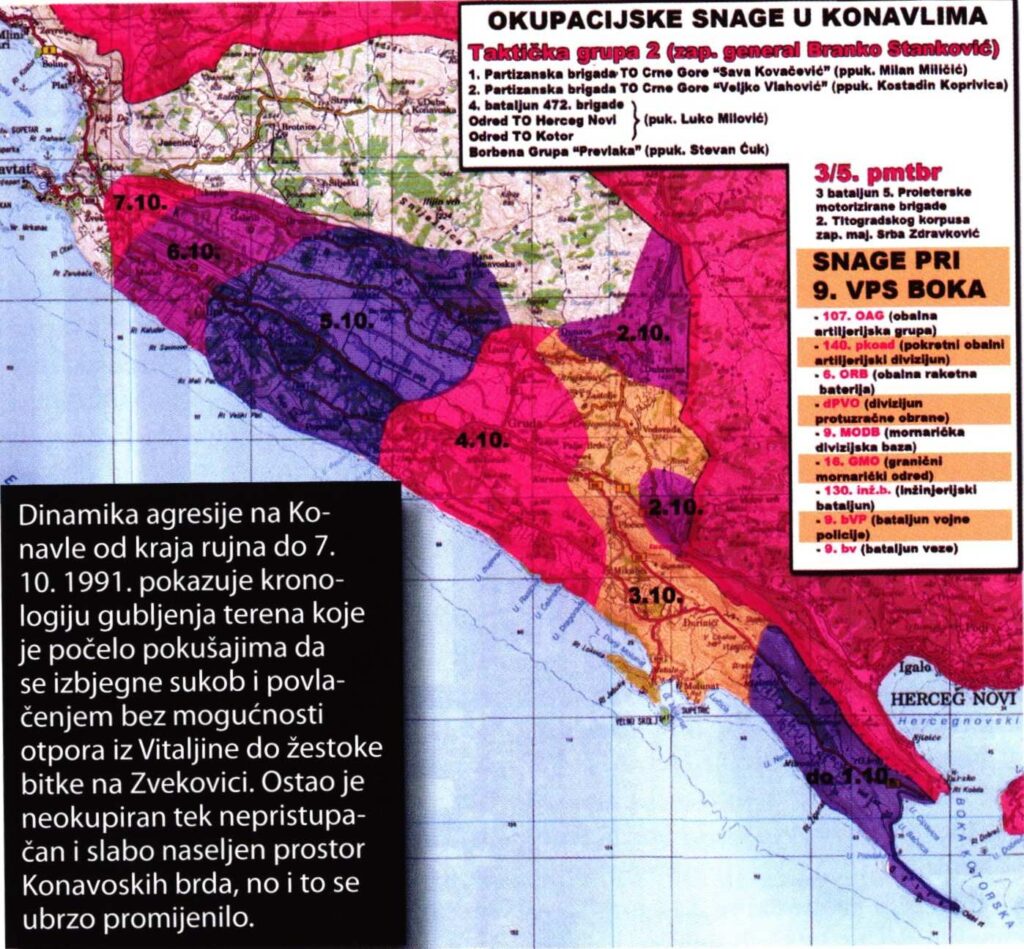

For the needs of the attack on Dubrovnik, the military top of the JNA set up Operational Group (OG) 2. It consisted of the 2nd Titograd Corps, the Naval Sector Kumbor, the Territorial Defence (TD) of Montenegro, the TD of Bosnia and Herzegovina from Eastern Herzegovina, the Montenegrin militia, several Chetnik groups, and air support was provided by the 97th Aviation Brigade from Mostar and 172nd Fighter-Bomber Aviation Regiment from Podgorica. The whole group was commanded by Colonel General Pavle Strugar. As part of OG 2, there were the 472nd Motorized Brigade from Trebinje and the 5th Motorized Brigade of Sava Kovačević from Nikšić, which were the JNA strike force, and the 2nd Titograd Corps raised two light infantry brigades, the 2nd Partisan Brigade of the TD and the 10th Brigade of TD Veljko Vlahović, and the 326th Mixed Artillery Regiment served for long-range artillery support. It is estimated that OG 2 had about 20,000 soldiers, 100 tanks, 50 armoured vehicles, 120 different large-calibre cannons and 100 aircraft.

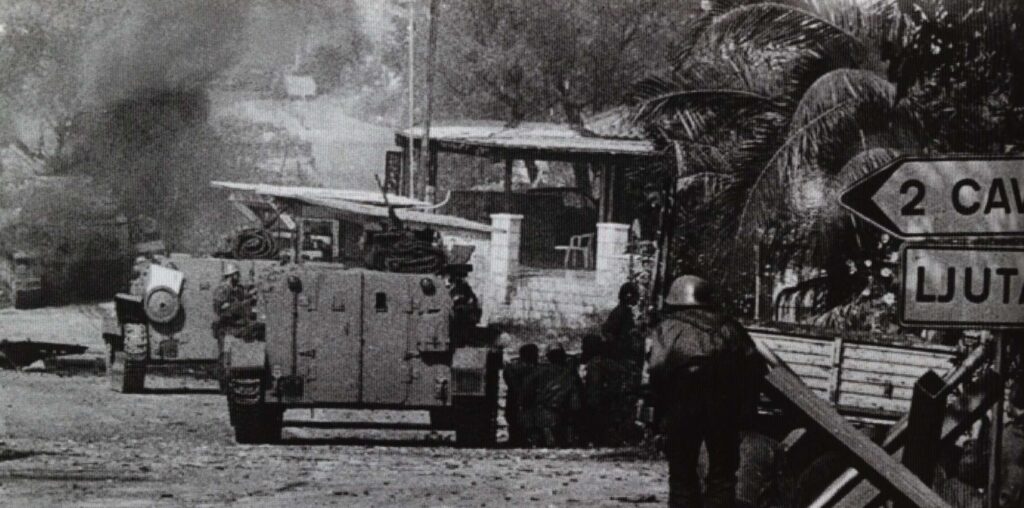

The JNA’s strategy was to cross Croatian territory with rapid incursions by armoured units and thus isolate and surround Croatian units. The plan for the attack on the south of Croatia was called Operation Dubrovnik by the JNA, and it was to take place in the following directions: Herceg Novi – Debeli Brijeg – Cavtat – Brgat; Trebinje – Ivanica – Dubrovnik; Zavala – Orahov Do – Slano. Unlike other routes marked by karst terrain with many cuts where an ambush can be made, Konavle could only defend itself on the narrow gorges of Prapratno and Debeli Brijeg, and as soon as the first line of defence was breached, more aggressors had the upper hand because Konavle valley favoured armoured units.

As early as 2nd September, JNA members opened machine gun fire on police officers in Vitaljina from a nearby hill. The following week, the border villages of Konavle were shelled, especially at night and early in the morning, and Yugoslav Navy (JRM) ships made frequent patrols towards Konavle’s coastline. All this forced part of the local population to leave their homes and go to Cavtat or elsewhere. Small Croatian forces were stationed in Prapratno, from where they responded to attacks with shelling. The commander of OG 2, Pavle Strugar, would later state that the JNA had to respond to Croatian mortar attacks and that an attack on Dubrovnik had been launched as a result.

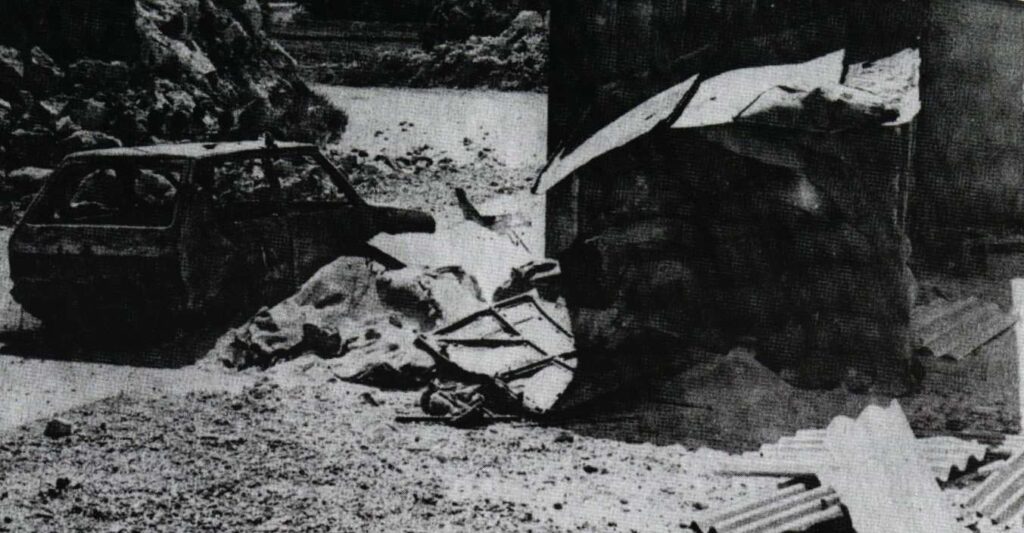

On October 1, 1991, a general attack was launched from all directions towards Dubrovnik. The first attempt to break through Prapratno was stopped, but the defenders had to withdraw after they found themselves in danger of being surrounded. After preparing the terrain with heavy artillery fire and the breakthrough of trench units in Konavle, members of the Veljko Vlahović Brigade stormed the highway and the border villages. Croatian forces were quickly forced to withdraw due to small numbers and insufficient weapons. However, due to the fear of 30,000 mercenaries, and due to the thoroughness of the shelling and looting, the aggressor needed a full 15 days before its troops entered Cavtat. Despite the heroic resistance of the people of Konavle on the October 4, when heavy artillery was positioned in the vicinity of Gruda and Ljuta, a day later the defence of Komaji gave way, and the reserve positions in Čilipi were defended by three-barrel grenades. The defenders tried to establish a defensive line east of the airport, but were pushed to Zvekovica. Troops from the Konavle hills retreated on October 6, and after the battle on October 7, Zvekovica fell.

With the declaration of Croatian independence on October 8, a truce was signed. Cavtat was full of refugees, so the European Community tried to prevent the Yugoslav People’s Army from entering Cavtat, but negotiations failed. With the entry of the aggressor into Cavtat on October 15, the occupation of Konavle was completed. Men of military ability were taken to a camp in Morinj, but small guerrilla forces from Konavle continued to fight, hiding in the caves of the Konavle hills.