Migration and travel for a diverse range of reasons, mostly economic, can be traced back to prehistoric times. However, leisure travel, originally reserved for a very limited number of people, has today become a widespread phenomenon. It was once practiced among members of higher social status, from Roman times until the 17th century, when traveling in Europe and the so-called Grand Tour, becomes part of the classical education of young English aristocrats. As early as the 18th century, this custom of travelling for several months, and sometimes for many years, to get acquainted with the art and culture of classical civilizations was adopted by members of the nobility of other European countries.

The main goal of this great journey was Rome, but during the 18th and 19th centuries, interest spread to Dalmatia. These travellers left a legacy of numerous drawings and literary works dominated by the ruins of ancient monuments and inspired by the effort to discover a new, hitherto unknown world.

New forms of transportation in the 19th century, steamships and trains, revolutionised not only trade but also reduced travel costs and making them more affordable. On this track, the railway can be considered a generator of the first mass tourist trips.

From the letters of Đorđe Bijelić addressed to Vlaho Bukovac, we learn that at the beginning of the century a few occasional travellers came to Cavtat, who Bijelić introduced to the cultural and natural sights of the place, and among other things showed them Vlaho Bukovac’s artist studio.

The phenomenon of tourism in those years became increasingly global, and with it the Czech interest in investing in tourist infrastructure on the Adriatic grows. In 1912, the Dubrovnik Bathing and Hotel Association was founded in Prague, of which Vlaho Bukovac was a member of the Supervisory Board. Thanks to that company, several boarding houses and hotel complexes were opened on the coast in Župa, and Bukovac advocated the purchase of land in the Cavtat area, something which he repeatedly wrote to his brother Jozo about, but also to Marija Bogišić Pohl, thinking that she could find people to sell land to build a hotel. However, Bukovac’s efforts were never realised. Interest in tourist visits to Cavtat obviously grew because in 1924 the Society for the Development of Cavtat and its surroundings and the improvement of foreign traffic in Cavtat was founded, and in 1936 the Municipal Tourist Board was established as part of the wider Alliance for Tourism Promotion.

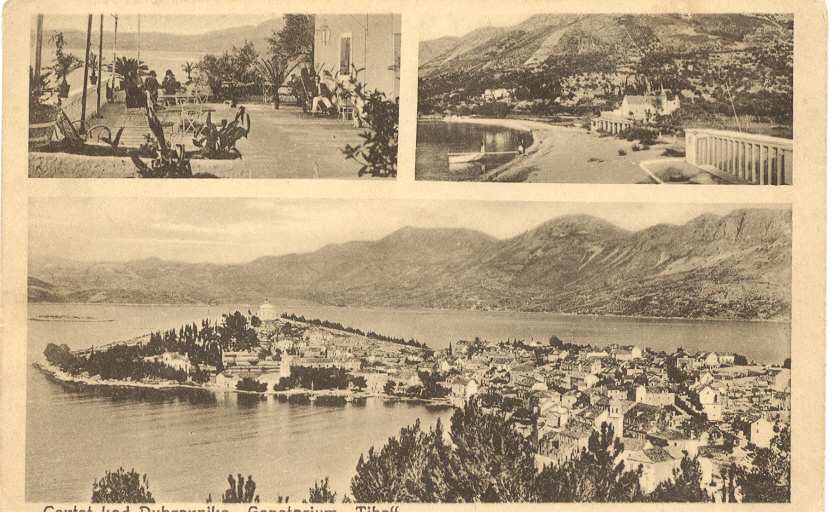

Cavtat was connected to Dubrovnik by several daily steamboat lines, so it was a frequent choice for day trips. The intensity of railway traffic also contributed to the development of tourism, so that in the 1930s there were several boarding houses and restaurants in Cavtat offering accommodation and food.

In addition to Pansion Koletić, which had 11 rooms, and Pansion Novaković with 45 rooms, accommodation could also be found in the Granić and Balkan restaurants, as well as in many private rooms.

After the Second World War, Pansion Novaković was nationalized and turned first into an orphanage, and then into a health resort for children, and a similar fate befell other Cavtat boarding houses and restaurants.

Many private houses were also nationalised and then repurposed for tourism. The family house of Štefi Račić thus became the Supetar Hotel, and Vila Banac a resort of the Macedonian government, and later an annex of the Hotel Makedonija.

It is interesting that the later construction of large hotel structures such as Epidaurus, Albatros and Croatia will be the reason for conducting systematic archaeological research in the area of ancient Epidaurus. It is a pity that this mass tourism of the 1960s and 1970s did not have the understanding to incorporate these cultural monuments into its offer.